This article is the second in a two-part series on the legacy of the 1912 election and the lessons it holds for this year’s presidential contest. The first article traced the 1912 campaign and its parallels to today.

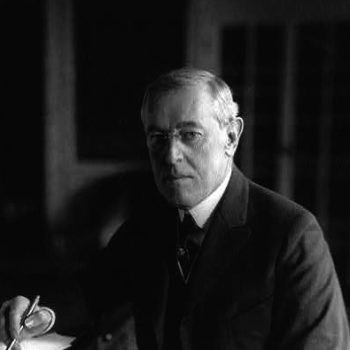

With the 2012 presidential campaign well underway, it pays to revisit the election of 1912 and its aftermath, not only because of the strange power that anniversaries exert upon the imagination but also for the numerous lessons this pivotal election holds for contemporary politics. The 1912 campaign mirrored much of what we already see in this year’s contest: a divisive political climate, a focus on economic-justice issues such as inequality and the political power of corporations, and a lack of cohesion in the Republican party. Equally important lessons are gleaned from the election’s outcome, which put Woodrow Wilson in the White House after a sophisticated rhetorical contest that clarified his vision for American democracy and shaped the policies he devised to achieve it. Numerous elements of our contemporary political system can be traced to Wilson’s election and the changes he implemented during his presidency.(a)

During the sixty-third Congress of 1913-14, Wilson pushed through a suite of reforms embodying his campaign promise to level the playing field of American economic life.1 His New Freedom initiatives rationalized the tariff, reined in the corporate monopolies, established the Federal Reserve, and created non-partisan bodies like the Federal Trade Commission and the Tariff Commission, empowered to interpret the laws in future contexts as well as suggest new legislation to Congress.2 Even after his initial program was largely achieved, Wilson stayed committed to an interventionist yet experimentalist, as opposed to dogmatic, politics. Convinced that the New Freedom reforms alone could not reinvigorate American democracy, he backed federal lending to cash-poor farmers, a redistributive income tax, and child labor laws; vetoed discriminatory immigration legislation; and eventually supported a national women’s suffrage amendment.(b) One tragic omission from the list of struggling Americans Wilson advocated for was African Americans, who never earned his sympathy the way laborers, immigrants, and women eventually did. This failure is all the more striking given Wilson’s efforts to reduce social stratification in America by establishing worker-friendly bureaucracies to oversee the nation’s wartime economic mobilization beginning in 1917.

As his interest in progressive social legislation expanded, Wilson in many ways fulfilled the promises made by his rival in 1912, Theodore Roosevelt, who had advocated direct state intervention to address the nation’s problems. Indeed, it can be argued that Wilson helped lay the grounds for the modern American welfare state that emerged a quarter-century later under Franklin Roosevelt.3 For one thing, Wilson contributed greatly to the power of the executive branch. He considered the presidency the only office that represented the whole people and constantly reminded both Congress and the people themselves of the fact. Although Wilson’s strong administrative state was weakened after the Republicans regained the White House in 1920, it provided both a general template and several specific policy models for the New Deal.

Another important legacy Wilson left to the New Dealers was his nomination and dogged support of Louis Brandeis to the Supreme Court in 1916.(c) Brandeis was far from a yes-man for FDR’s administration, but he resolutely supported two basic New Deal notions: first, that government’s job was to foster liberty and equality in an ever-changing society, rather than enforce anachronistic legal and institutional constraints on the meaning of those ideals; and second, that solidarity among diverse groups and interests was crucial to achieving both liberty and equality in a highly interdependent society. By carefully scrutinizing rather than reflexively supporting many New Deal initiatives, Brandeis remained more progressive, in the Wilsonian sense, than many New Dealers who claimed progressive roots.

Beyond his influence on the New Deal era, we still live with Wilson’s legacy today. His administration was the first to raise revenue through a federal income tax and later became the first to support using the income tax to redistribute wealth. The Wilson administration was also the first to recruit academic experts to advise on foreign policy matters in a systematic fashion, establishing the so-called “Inquiry” to counsel on the World War I peace process.(d) Even the familiar yet powerful image of the president speaking directly to the people’s elected representatives in Congress derives from Wilson’s tenure in office. Before he instituted the practice of presenting his State of the Union address in person in 1913, no president had personally addressed Congress at the Capitol since 1801.

The fact that Wilson’s election in 1912 left such an important institutional and even constitutional legacy is perhaps one reason Americans today are still fighting many of the same ideological battles that raged a hundred years ago. Arguably, those battles persist because the political culture of American progressivism failed to take root as permanently as the strong executive branch and active government that historians and political scientists trace to Wilson and the progressive movement more generally. Without a broadly informed, politically engaged, prudently skeptical yet civically minded public willing to join in tolerant debate over the goals that should guide policy, as envisioned by the progressives, a strong state lacks accountability and misspends its energies. Inquiring into the origins of the system within and about which we debate today can provide the historical perspective to conceive a more accountable, less wasteful alternative, spurring more imaginative solutions to present problems. Moreover, recovering certain modes of analysis and habits of discourse that characterized important wings of the progressive movement might be a small start toward transcending today’s highly ideological, inflexible, and intolerant politics.

Endnotes

- For a thorough exploration of the intellectual roots of Wilson’s New Freedom platform, see Trygve Throntveit (2008) “‘Common Counsel’: Woodrow Wilson’s Pragmatic Progressivism, 1885-1913,” in Reconsidering Woodrow Wilson: Progressivism, Internationalism, War, and Peace, edited by John Milton Cooper Jr., Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 25-56.

- The best overviews of Wilson’s legislative achievements during the sixty-third Congress include: Arthur S. Link (1956) Wilson: The New Freedom, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; and John Milton Cooper Jr. (2009) Woodrow Wilson: A Biography, New York: Knopf.

- Stephen Skowronek (1982) Building a New American State: The Expansion of National Administrative Capacities, 1877-1920, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Sidney M. Milkis & Michael Nelson (2011) The American Presidency: Origins and Development, 1776-2011, 6th edition, Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Sidenotes

- (a) Surveys of historians typically rank Wilson among the ten most important and successful U.S. presidents. Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, and Franklin D. Roosevelt usually lead the pack.

- (b) After previous attempts failed on constitutional grounds, the modern personal income tax was implemented after the ratification of the sixteenth amendment in 1913, Wilson’s first year in office. By the end of Wilson’s second term in 1921, the tax rate ranged from 4% for those in the lowest bracket to 73% for the highest earners.

- (c) Louis Brandeis was the first Jewish person ever nominated to the Supreme Court. He sat on the bench from 1916 to 1939.

- (d) Several of the scholars involved in the Inquiry went on to found the Council on Foreign Relations, one of the most influential foreign policy think tanks in the world.