Alongside their roles as workers, pets, and food, domesticated animals have long been an invaluable tool for genetic researchers.(a)

Cows, chickens, dogs, and other domesticated animals represent fertile ground for genetic research for two main reasons. First off, they tend to be very highly inbred, meaning that there is relatively little genetic variation within a given breed. This lack of genetic diversity makes it much simpler to identify genetic changes linked to a given trait. Secondly, they have already been artificially selected for traits that are interesting to humans for one reason or another.(b) In the case of dogs and other pets, a number of the traits selected for are aesthetic: coat length, size, body shape, and distinctive physical characteristics humans consider attractive.

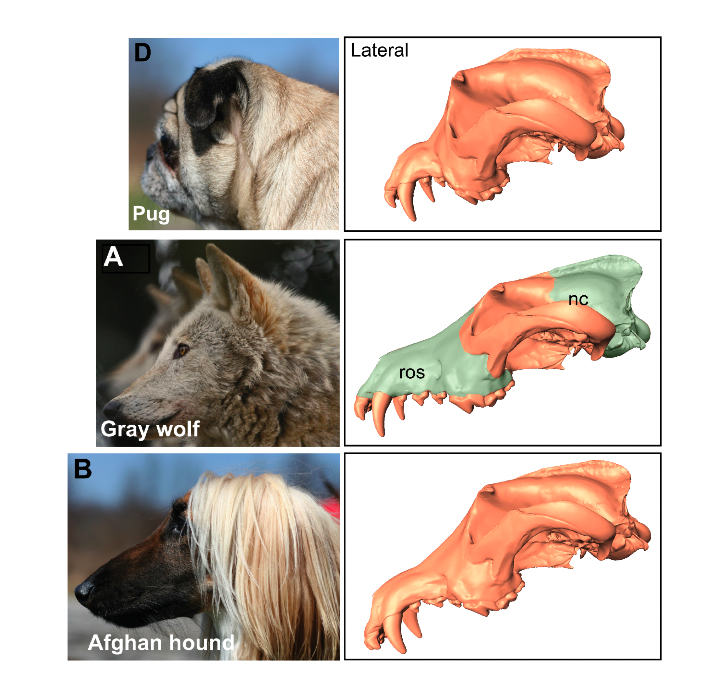

A new paper in PLoS Genetics1 examines the genes that drive the brachycephalitic skull shape, the shortened head found in Bulldogs, Pugs, Pekingese, and other dog breeds.(c) Using a common tool for genetic analysis known as a Genome Wide Association Study, the authors identified several regions of the genome linked to the short-headed appearance. They found a single mutation in a gene called Bone Morphogenic Protein 3 (BMP3) that was present in almost every short-faced dog breed. The authors predicted that this mutation would decrease the function of the gene, resulting in a shorter jaw. When they artificially reduced the activity of this gene in fish, they found severe abnormalities in jaw development. Though experiments in mice from a separate study were less clear, the results in fish point to a key role for BMP3 in facial development.

It remains to be seen what role this gene plays in human facial development, although DNA deletions in or near BMP3 have been found in humans with craniofacial abnormalities. Regardless, if you have a Pug or a French Bulldog running around the house, you can now look down into its funny little face and know that it is the BMP3 gene that made it that way.

Jesse Lyons received his PhD in Biomedical Sciences from the University of California San Francisco, where he used molecular and cellular biology to understand the genetic basis of melanoma. Dr. Lyons is currently completing a joint post-doc at MIT and Harvard/Massachusetts General Hospital, using systems biology to study inflammatory diseases.

Image Credits: Cover photo of pug from Poi Photography. Article figure of canine skull shapes from PLoS Genetics, adapted by Jesse Lyons. Both under a CC license.

Endnotes

- Jeffrey J. Schoenebeck, Sarah A. Hutchinson, Alexandra Byers, Holly C. Beale, Blake Carrington, Daniel L. Faden, Maud Rimbault, Brennan Decker, Jeffrey M. Kidd, Raman Sood, Adam R. Boyko, John W. Fondon III, Robert K. Wayne, Carlos D. Bustamante, Brian Ciruna, Elaine A. Ostrander (2012) “Variation of BMP3 Contributes to Dog Breed Skull Diversity,” PLoS Genetics, 8(8): e1002849, doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002849.

Sidenotes

- (a) Charles Darwin himself wrote an entire book devoted to the subject: The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication.

- (b) Whereas natural selection relies on survival as the filter by which genetic changes are spread through a population, in artificial selection, the filter is us.

- (c) The continued push for shorter, flatter faces in Bulldogs and other breeds can have serious health consequences, such as problems breathing and eating.