This article was produced as part of The College & University Research Collaborative, an innovative project to bring academic research and expertise to Rhode Island policymakers.

On March 23, 2010, President Obama signed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) designed to increase health insurance coverage among the U.S. population. A key component of the law was an expansion of Medicaid(a) to cover up to 17 million more low-income individuals. After a series of legal challenges, in 2012 the Supreme Court upheld many parts of the Affordable Care Act but ruled that states could not be required to expand Medicaid coverage.(b) Since then, just over half of states have chosen to expand Medicaid, while the remainder have not.2

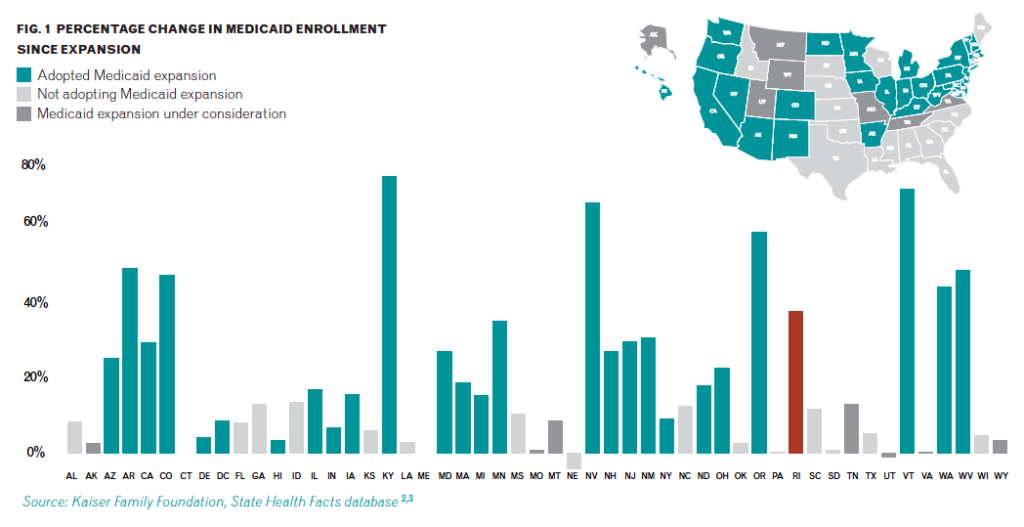

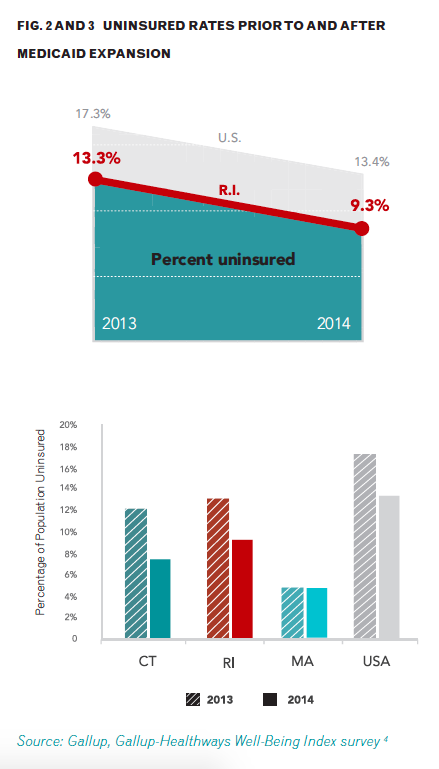

The decision whether or not to expand Medicaid has had a substantial impact on access to health care coverage, and states like Rhode Island that chose to expand have had significantly higher increases3 in the percentage of their population covered.(c) Since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, enrollment in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) in Rhode Island increased 37%, from 191,000 to 262,000.3 Rhode Island effectively reduced its total uninsured population to an estimated 9.3% by mid-2014, from 13.3% prior to the implementation of the ACA (the current national figure is 13.4% and was 17.3% before the ACA).4 Overall, uninsured rates still vary widely from state to state, from 24.0% in Texas to 4.9% in Massachusetts.4

If we look simply at the number of people covered, Rhode Island’s decision to expand Medicaid was a success. But the arguments for the expansion of health insurance made by the Obama administration were not just moral – they were also economic. The Council of Economic Advisors argued that the lack of health care coverage among many Americans has a significant negative effect on national economic prosperity.5 On the other side, critics and political leaders in states that rejected the expansion worried that enlarging Medicaid would hurt state economies and strain state budgets.

Did Rhode Island make the right choice by expanding Medicaid? What will the impact of that decision be on the state’s economy? To answer this question, we analyze how health insurance coverage rates and health care spending levels affected economic growth in 48 states over 23 years. Our research indicates that the expansion of health insurance coverage can help Rhode Island’s economy, but only if the state controls costs.

The Relationship between Health Coverage and Economic Growth

Despite the lively debate in the popular press over the potential economic consequences of expanding health care coverage, few studies have directly investigated the effect of universal or near-universal health insurance on employment and economic growth. Instead, the academic literature to date largely relies on the assumption that because greater access to health insurance improves health and better health leads to economic growth, health insurance coverage should have a positive economic effect. This, however, does not account for the potential negative effects of health care costs.

The economic benefits of having a healthy population are clear: workers are more productive, less likely to miss work due to illness or disability, and less likely to leave the workforce due to illness or death.(d) Several studies indicate that improved health outcomes are “one of very few robust predictors of economic growth,”7 and research suggests that health improvements since the 1970s added approximately $3.2 trillion per year to national wealth in the United States.8 The studies are also clear that health insurance coverage can help create a healthier population. Quality health insurance has been shown to decrease the onset of avoidable illnesses, increase access to care for treatable illnesses, and decrease the likelihood that relatively minor illnesses become severe.9 Health care coverage, however, is not without its costs, and these costs must be balanced against the economic gains that come from better health.

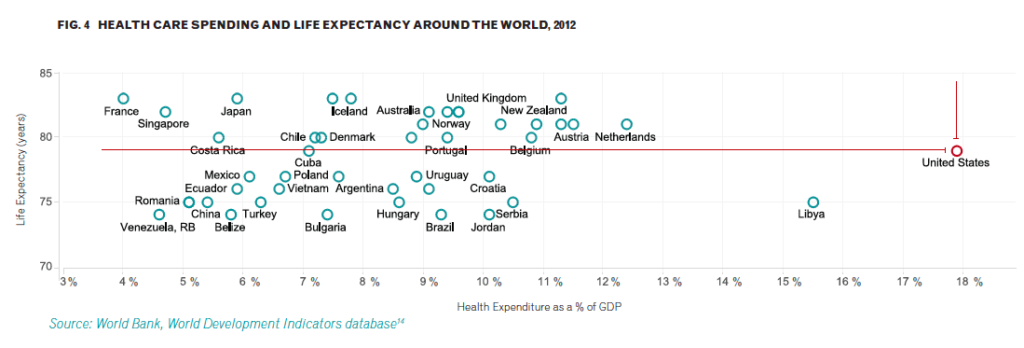

What is less clear from existing research is the overall effect of health care spending on economic growth. While some literature suggests that it can act as an economic stimulus by increasing both wages and the number of jobs in the health care sector,10 escalating health care costs can also be a serious drag on economic growth.(e) Health insurance premiums, for instance, have risen by 69% since 2004,11 and studies have documented that premium increases meaningfully cut into wages and raise the likelihood of being unemployed or underemployed.12 For state governments, increasing health costs can result in higher taxes, more borrowing, or cuts to other important programs and services, including economic growth investments such as education and infrastructure.13 It’s also important to consider that health care spending is not necessarily associated with better health outcomes: The United States spends far more per person on health, yet has a lower life expectancy, than many other developed nations.

Our Research on the Economic Impact of Health Coverage and Health Spending

While existing research offers good reason to believe that expanding health care coverage can help the economy by making workers healthier and therefore more productive, it also suggests that, to the extent that enlarging coverage increases government spending, the net effect on the economy may be negative. Our research takes into account both of these factors – expanded coverage and increased spending – by looking directly at the connection between health care coverage, health care spending, and economic growth.

Using data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the U.S. Census, we analyze how health insurance coverage and health care spending affected economic growth (in terms of GDP and total employment) in the lower 48 states from 1988 to 2010.15 We compare rates of private and public coverage and analyze coverage by age group, with a particular focus on the working-age population of 18 to 65 year olds.(f) We examine health care spending both per capita and as a percentage of state GDP, and we break it out into private spending and government spending on Medicare, Medicaid, and military health care (for both active duty servicemembers and veterans). We also include a number of control variables in our analysis to ensure our findings are not driven by unobserved factors.

Economic Growth and Health Insurance Coverage

Our analysis indicates that enrollment by working-age adults in government-sponsored health insurance programs – including Medicaid, Medicare, and military health plans – all increase economic growth. Our estimates suggest that a one percentage point increase in public coverage of the working-age population increases annual real GDP growth by 0.08 percentage points and increases employment growth by the same 0.08 percentage points. However, our analysis indicates that there is no significant relationship between private coverage for the working-age population and economic growth.(g)

To understand the significance of these findings, consider Medicaid, the public health insurance program over which states have the most control (because it is jointly funded and administered by the federal and state governments). In 2013, only 13% of working age adults in Rhode Island were covered by Medicaid, close to the national average of 12%.16 However, enrollment surged in the first year of the Medicaid expansion, with total enrollees (including children and the elderly) increasing 37% by November 2014.3 Although the data do not indicate what share of the new enrollees are working-age adults, a conservative estimate suggests that this increase in Medicaid enrollment included a five percentage point increase in public coverage of the working age population, bringing the rate to 18%. The results of our analysis suggest that this could lead to a 0.4 percentage point increase in state per capita GDP growth and employment growth rates.(h)

Economic Growth and Health Care Spending

Our analysis indicates that the more individuals and businesses spend per person on health care, the less economic growth states experience (the job growth rate is not affected). A one percent increase in private health care spending is associated with a 0.05 percentage point decrease in a state’s GDP growth rate. This is probably due to the “crowding-out” effect of health care spending, in which money that businesses spend on health care is money they don’t use to increase wages, hire new employees, or invest in new product development.12 Likewise, the more individuals pay in health care costs, the less likely they are to save or to spend that money on goods, services, and investments such as higher education and the more likely they are to go into debt or file for bankruptcy.17

In contrast to private spending, increased government spending on health care does not appear to affect economic (GDP) growth. However, higher public spending, especially Medicaid spending per enrollee, is associated with slower job growth. This may be due to the fact that Medicaid spending and spending on job growth investments such as education and infrastructure are typically inversely related. For example, one study found that each additional dollar that states spend on Medicaid results in a six to seven cent cut in higher education appropriations.13

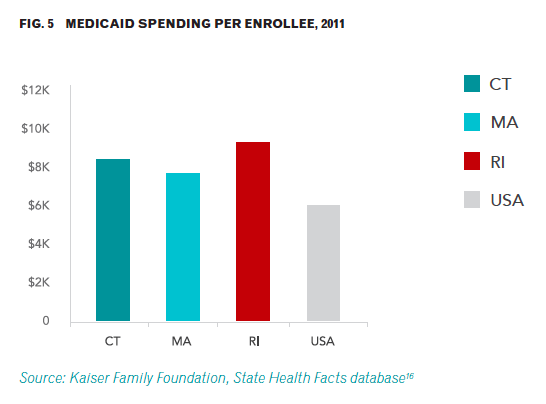

Our analysis indicates that a one percent increase in Medicaid spending per enrollee reduces a state’s employment growth rate by 0.008 percentage points per year. In 2011, the last year for which national data are available, Rhode Island spent $9,247 per enrollee on Medicaid, the second-highest rate in the country.18 If the state could reduce Medicaid spending to the 2011 national average of approximately $5,790 per enrollee – about a 37% decrease – the employment growth rate could be increased by as much as 0.29 percentage points.(i) This represents a significant potential impact given that Rhode Island’s employment growth rate averaged around 0.4% annually over the past decade.

Controlling Health Care Costs

Reducing health care costs while maintaining quality care – and thus reaping the economic benefits of expanded coverage – is a complicated endeavor.(j) One option is managed care programs, in which health care is coordinated, typically through a patient’s primary care physician, to manage usage, quality, and costs. While evidence on the impact of managed care is mixed, research suggests that enrolling high-cost populations in these programs has the most potential to save money.19 Rhode Island already has a managed care program that includes almost three-quarters of its Medicaid population. However, over half of the state’s Medicaid spending is on the 23% of people not covered by the program.20

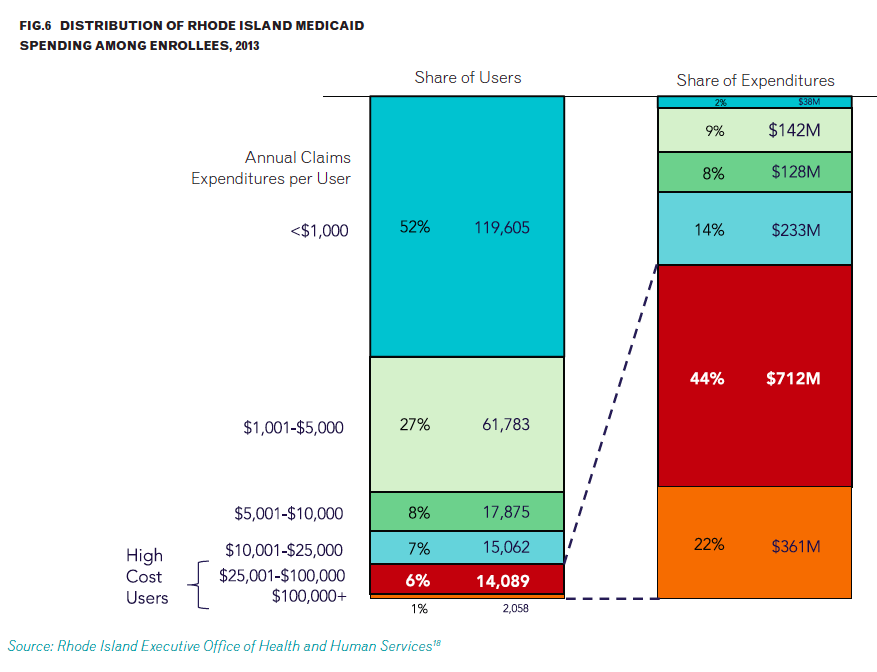

In fact, Medicaid spending varies widely from person to person and is extremely concentrated among certain groups. In Rhode Island, approximately 7% of enrollees account for about 66% of Medicaid expenditures, costing an average of $66,396 per person in 2013.(k) Complex care management is a promising approach that focuses on controlling costs for these kinds of high-expenditure populations. In a complex care management program, a team of specialized social workers, nurses, and care managers identifies high-cost patients and determines what is driving their use of medical services. The team then works directly with these patients to manage and coordinate their care and reduce the incidence of hospitalization and emergency room visits.

While complex care management takes concerted effort, recent research suggests that the costs may be worth it. One study of an initiative in St. Louis that included long-term, in-person oversight of care found that the program “reduced hospitalizations by 12% and monthly Medicare spending by $217 per enrollee – more than offsetting the program’s monthly $151 care management fee.”21 Camden, New Jersey’s “Camden Coalition” has served as a model of this type of cost control, as have programs at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston that are designed to meet the needs of high-expenditure cases. Recent evidence from these programs suggests that emergency room visits by high-expenditure individuals dropped, as did overall costs for these patients.22

Is Rhode Island on the right track?

Our research suggests that Rhode Island is on the right path in joining 27 other states to expand Medicaid coverage through the ACA. Increased health insurance coverage of the working age population through government programs like Medicaid is associated with stronger GDP and employment growth. That said, Rhode Island currently spends more on Medicaid per enrollee than most states, and higher spending can drag down job growth. Decreasing the amount spent per person on health care would provide an opportunity for Rhode Island to fully harness the economic benefits of expanding health insurance coverage and address the state’s high unemployment rate.

Massachusetts, which began health insurance reform in 2007, well before the rest of the country, can serve as a model. They decreased their uninsured rate from 10% in 2004 to 4% by 2012, largely by expanding Medicaid eligibility and increasing Medicaid enrollment from 17% in 2004 to 26% in 2010. Over that same time period, however, they reduced their Medicaid spending from $9,600 (similar to Rhode Island’s 2011 level) to $7,500 per enrollee.23 Rhode Island has begun to reduce its costs per Medicaid enrollee, at a rate of about 1.5% per year from 2009 to 2013.20 If the state can continue to make strides in expanding coverage and cutting costs, it can both improve the health of its citizens and grow its economy.

Endnotes

- Congressional Budget Office (2012) “Updated Estimates for the Insurance Coverage Provisions of the Affordable Care Act,” and (2014) “Updated Estimates of the Effects of the Insurance Coverage Provisions of the Affordable Care Act,” Washington, DC.

- Kaiser Family Foundation (2015) Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision [data files].

- Kaiser Family Foundation (2014) Total Monthly Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment [data files].

- Dan Witters (2014) “Arkansas, Kentucky Report Sharpest Drops in Uninsured Rate,” Gallup, August 5.

- Council of Economic Advisers ( 2009) The Economic Case for Health Care Reform, Washington, D.C.: Executive Office of the President.

- Jack Hadley (2003) “Sicker and Poorer—The Consequences of Being Uninsured: A Review of the Research on the Relationship between Health Insurance, Medical Care Use, Health, Work, and Income,” Medical Care Research & Review, 60(2): 3S-75S. Sandra L. Decker, Jalpa A. Doshi, Amy E. Knaup, and Daniel Polsky (2012) “Health Service Use among the Previously Uninsured: Is Subsidized Health Insurance Enough?” Health Economics, 21(10): 1155–1168.

- Marc Suhrcke & Dieter Urban (2010) Are cardiovascular diseases bad for economic growth?, Health Economics, 19(12): 1478-1496.

- Kevin M. Murphy and Robert H. Topel (2006) “The Value of Health and Longevity,” Journal of Political Economy, 114(5): 871-904.

- Jill Bernstein, Deborah Chollet, and Stephanie Peterson (2010) “How Does Insurance Coverage Improve Health Outcomes?” Mathematica Policy Research, Reforming Health Care Issue Brief, number 1.

- Mark V. Pauly (2004) “Should We Be Worried About High Real

Medical Spending Growth In The United States?” Health Affairs, 22(3, supp.): W3-15. - Kaiser Family Foundation (2014) “2014 Employer Health Benefits Survey,” Menlo Park, CA.

- Katherine Baicker and Amitabh Chandra (2005) “The Labor Market Effects of Rising Health Insurance Premiums,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper, number 11160. Benjamin D. Sommers (2005) “Who Really Pays for Health Insurance? The Incidence of Employer-Provided Health Insurance with Sticky Nominal Wages,” International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics, 5(1): 89-118.

- Thomas J. Kane, Peter Orszag, David L. Gunter (2003) “State Fiscal Constraints and Higher Education Spending: The Role of Medicaid and the Business Cycle,” Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, Discussion Paper, number 11. Neeraj Sood, Arkadipta Ghosh, and J. Escarse (2007) The Effect of Health Care Cost Growth on the US Economy, Washington, D.C.: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- World Bank (2014) “Health Expenditure, total (% of GDP),” World Development Indicators [data files].

- Our data include many different types of health care spending in order to verify the relationship between different health care investments by the state and private entities and state economic growth. These include overall health care spending; specific spending for Medicaid, Medicare, and military health care by the government; and health care expenditures in the private market.

- Kaiser Family Foundation (2013) Medicaid Coverage Rates for the Nonelderly by Age [data files].

- David U. Himmelstein, Deborah Thorne, Elizabeth Warren, and Steffie Woolhandler (2009) “Medical Bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: Results of a National Study,” The American Journal of Medicine, 122(8): 741–746. Ryan Jaslow (2012) “One-third of young adults face medical bill troubles, debt,” CBS News, June 8.

- Kaiser Family Foundation (2011) Medicaid Spending per Enrollee (Full or Partial Benefit) [data files].

- Michael Sparer (2012) “Medicaid managed care: Costs, access, and quality of care,” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Research Synthesis Report, number 23.

- Rhode Island Executive Office of Health and Human Services (2014) “Rhode Island Annual Medicaid Expenditure Report,” Providence, RI.

- Deborah Peikes, Greg Peterson, Randall S. Brown, Sandy Graff, and John P. Lynch (2012) How changes in Washington University’s Medicare coordinated care demonstration pilot ultimately achieved savings, Health Affairs, 31(6): 1216-1226.

- Atul Gawande (2011) “The Hot Spotters,” New Yorker, January 24.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts (2014) State Health Care Spending on Medicaid, 50 State Data [data files].

Sidenotes

- (a) Medicaid is the government’s health insurance program for low-income individuals; it is jointly funded and administered by the federal and state governments. Medicare, on the other hand, is the federal health insurance program for individuals over age 65 and people with disabilities.

- (b) After the Supreme Court decision, the Congressional Budget Office revised its estimates and predicted that 13 million people, rather than 17 million, would gain coverage under Medicaid and CHIP by 2018.1

- (c) The ACA expanded Medicaid eligibility from people living at or below the federal poverty line ($11,670 a year for one person, $23,850 for a family of four) to people earning up to 138% of the poverty line ($16,105 a year for one person, $32,913 for a family of four). Funding for the expansion is provided by the federal government.

- (d) Reducing the prevalence of particular health conditions has been shown to increase personal earnings by 15% to 20%, while poor health has been identified as a primary reason people leave the workforce early and file for social welfare programs, particularly Disability (SSI).6

- (e) While the Affordable Care Act originally had provisions included to help control the increase in health spending in the United States, these items were cut in an attempt to gain passage as people became concerned about the government making health care decisions instead of doctors.

- (f) Private, employer-provided insurance could be linked to economic growth simply because it is a proxy for employment. Public health insurance programs, on the other hand, often cover low-wage workers and the unemployed.

- (g) There are a number of potential reasons why public coverage impacts economic growth but private coverage does not, many of which have to do with the different populations covered by the two. Almost everyone with private coverage, for example, already has a job, so health coverage will not increase their labor supply.

- (h) From 2000 to 2013, per capita GDP growth in Rhode Island averaged less than 1.3% and employment growth averaged less than 0.4% according the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Thus a 0.4 percentage point increase in the growth rates would be quite large.

- (i) Like Medicaid coverage rates, spending per enrollee varies significantly from state to state, from a low of $3,728 in Nevada to a high of $9,474 in Alaska (as of 2011).18

- (j) Restricting care is one obvious way to reduce costs, but doing so would be counterproductive because the economic benefits of expanded insurance coverage come from having healthier, more productive workers.

- (k) 79% of Medicaid enrollees in Rhode Island cost Medicaid less than $5,000 a year. The average annual expenditure for this group is $992 per person annually, meaning that the top 7% of Medicaid users cost almost seventy times as much per person as those in the bottom 79%.20