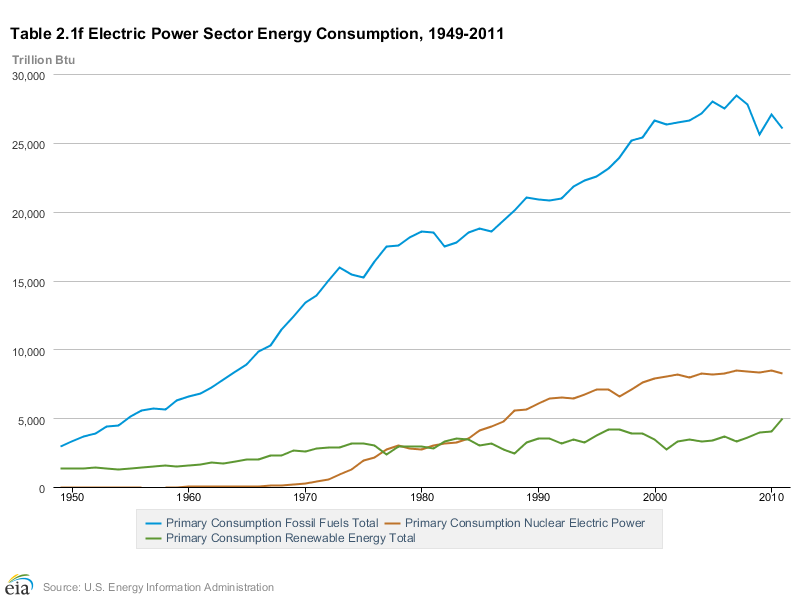

Despite concerns about the long-term sustainability and environmental impact of traditional energy sources such as oil, coal, and natural gas, as well as nuclear power, 87% of all electricity in the U.S. still comes from non-renewable sources.(a)

In a number of states, policymakers impatient with the slow pace of change have taken a more active role in steering private industry toward reliance on clean energy. Renewable portfolio standards (RPS), which require utility companies to produce a certain share of their electricity from specific sources, have been one of the most direct tools for altering where our electricity comes from. These laws offer an interesting case study of both how government policy can impact private industry and how businesses respond to new regulation.

Sources Of Energy Used In U.S. Electricity Production, 1949 to 2011. Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

Easy access to coal and natural gas led U.S. electric utilities, many of which are privately owned, to choose the most reliable and cost beneficial technologies, which often happen to be non-renewable sources. This strategy led the development and dominance of non-renewable electricity from early on in the industry’s history. Today only 8% of our electricity comes from hydroelectric sources (water power) and 5% from other renewable sources like wind, solar, geothermal, and biomass.(b)Renewable portfolio standards, which began in 1983 and took off over the past decade, attempt to steer the industry in a different direction

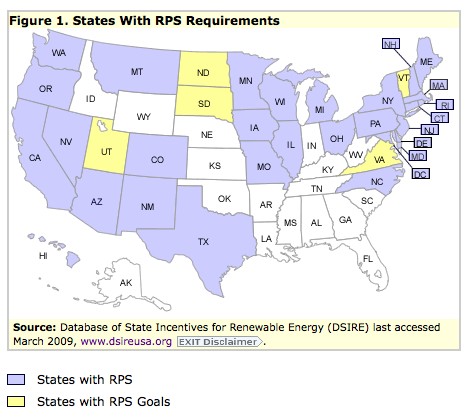

As of 2012, binding renewable portfolio standards have been passed in twenty-nine states, Washington D.C., Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, while another eight states and two territories have voluntary renewable goals. The goals vary from state but typically specify:

– the amount of renewable electricity that must be produced;

– what sources are classified as renewable, possibly including solar, hydroelectric, wind, biomass, geothermal and nuclear;

– whether the renewable energy must come from within the state;

– the date by which firms must meet these targets;

– and whether firms can buy renewable electricity credits from other firms across state lines.

A state-by-state summary of RPS found targets ranging from 12.5% to 40% of electricity from renewable sources by between 2015 and 2030. Though the details differ across states, the overall goal is the same: to promote the use of renewable electricity and increase jobs in the state by developing the renewable energy sector.(c)

States with Renewable Energy Portfolio Standards (RPS), as of 2009. Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

Two main factors explain whether a state is likely to adopt renewable portfolio standards. The first is political ideology, which is not surprising since clean energy – and environmental protection more generally – have typically been considered liberal issues. Researchers Thomas P. Lyon and Haitao Yin found that the biggest predictor of the adoption of RPS by a state is the number of Democratic senators.1Interestingly, although one of the goals of RPS is to increase jobs in the clean energy sector, their research shows that the level of unemployment does not influence whether or not a state is likely to adopt the laws.

A second important factor is the power and interests of large utility firms within a state. Research by Adam R. Fremeth and Alfred A. Marcus tries to unpack the exact mechanism by which this dance between state policy makers and firms occurs by documenting the enactment of RPS in Minnesota.2 They find that it is difficult for the state to simply enact regulation to increase the use of renewable electricity without also negotiating with electricity providers. No one actor can effectively enact a standard; instead, it must be a negotiation between all the different agents involved, both private and public.

Though the earliest target deadlines in the laws have yet to expire, preliminary research suggests that certain forms of RPS policies have been successful in increasing reliance on renewable energy sources.3 On the whole, renewable portfolio standards have not increased overall U.S. reliance on renewable electricity, but states with stricter forms of RPS have seen incremental increases in renewable capacity. Effectiveness depends on the stringency of the laws; voluntary standards, those permitting trading, and those covering only certain types of utility companies were found to have a much weaker impact. Interestingly, one study also found that the impact of the laws was different for different kinds of energy sources. RPS encouraged geothermal and solar development but not wind and biomass.

For several years, advocates have been pushing for a national renewable portfolio standard. Given the success of certain forms of RPS in promoting renewable energy within states, the potential impact of a national law seems promising, depending on how the policy is structured. Some have even argued for the adoption of an international standard. The resistance to such measures is primarily political. How much of a role should the government play in pushing private industry toward more socially desirable policies? This classic liberal-conservative argument won’t be resolved any time soon, but it looks like in many states, renewable portfolio standards may be here to stay.

Endnotes

- Thomas P. Lyon and Haitao Yin (2010) Why Do States Adopt Renewable Portfolio Standards? An Empirical Investigation, The Energy Journal, 31(3): 133-157.

- Adam R. Fremeth and Alfred A. Marcus (2011) “Institutional Void and Stakeholder Leadership: Implementing Renewable Energy Standards in Minnesota,” in Stakeholders and Scientists: Achieving Implementable Solutions to Energy and Environmental Issues, edited by Joanna Burger, New York: Springer, p. 367-392.

- Gireesh Shrimali and Joshua Kniefel (2011) “Are government policies effective in promoting deployment of renewable electricity resources?” Energy Policy, 39(9): 4726–4741. Haitao Yin and Nicholas Powers (2010) “Do state renewable portfolio standards promote in-state renewable generation?”Energy Policy, 38(2): 1140–1149.

Sidenotes

- (a) This includes the 8% of electricity that comes from nuclear power, which is not generally considered a renewable energy source. There is some debate, however, over whether it should be classified as renewable. While nuclear energy produces little in the way of greenhouse gases, it does create toxic waste and requires the use of nonrenewable uranium for fuel.

- (b) In comparison to 13% in the U.S.,20% of worldwide electricity production now comes from renewable sources, primarily hydroelectric power. Leaders in the field include Norway (97% renewable), Brazil (88%), New Zealand (76%), Canada (64%), and Portugal (47%).

- (c) One prominent Obama administration initiative has been to promote green jobs in fields such as home energy efficiency improvement, renewable energy production, electric grid modernization, and clean transportation options. The 2009 economic stimulus bill included $90 billion for clean energy efforts, withmixed results.