On March 30th, the business journal The Economist ran a story describing the complexities of climate science modeling and offering an intricate scientific explanation of why air temperatures at the Earth’s surface have remained flat for the past 5 to 15 years while greenhouse gas emissions have continued to rise. And with this article as the flashpoint, the latest rhetorical battle on climate change began.

Despite the author’s quick assertion that this “does not mean global warming is a delusion” and that global average “temperatures in the first decade of the 21st century remain almost 1 degree Celsius above their level in the first decade of the 20th,” Rush Limbaugh used the article as proof that “global warming is a hoax.”(a) The National Review added that “the new climate deniers are the liberals who… have managed to miss the biggest story in climate science.” Scientists have offered clear explanations in the past for the lack of change in average surface temperature measurements and scrambled to clarify the complexities of the models that The Economist ambitiously tried to explain. Yet Ed Rogers of the Washington Post warned of “Obama and the Democrats’ attempts to control our lives via climate change policy.” A serious effort to explain the complexity of climate science was transformed into a contest of rhetorical destruction invoking politics, religion, fears, and conspiracy theories.

A Different Perspective on the Debate

Why is this so? Why did a scientific issue like climate change become so toxic, so caught up in what we call “the culture wars”? It is because the social debate around climate change is no longer about carbon dioxide and climate models. It is about values, culture, worldviews, and ideology. As physical scientists explore the mechanics and implications of anthropogenic climate change and try to convey their results to a skeptical public, they must recognize that their work is being evaluated by a population where upwards of two-thirds do not clearly understand the scientific process and fewer are able to pass even a basic scientific literacy test.(b) In discussing this issue, people hear far more than science. They hear an engagement with deeply held values and beliefs.

While frustrating to those in the physical sciences who expect their work to be judged by peer review and not public palatability, this response is something that social scientists can help us understand and address. The fields of psychology, sociology, anthropology and political science can help explain the cultural, cognitive and political reasons why people support or reject the scientific consensus that both the U.S. National Academies of Science and the American Association for the Advancement of Science officially state exists.

Social scientists are a relatively new voice in this public debate. To date, the academic perspective on climate change has mostly taken the form of physical scientists identifying and describing the problem and economists and policy experts developing potential solutions. These efforts have often been somewhat abstracted from messier questions about how the public views the issue of climate change and how they will respond to potential solutions. Social science offers valuable tools for answering these questions and understanding how to cultivate broad-based support for meaningful action on climate change.

The Source of the Schism

Recent social science research illuminates why climate change has joined issues such as evolution and stem cells in moving beyond the realm of science to become a social and cultural flashpoint. In a process that legal scholar Dan Kahan labels “cultural cognition,”1 people are influenced by group values and will generally endorse the position that most directly reinforces the connections they have with others in their social groups.(c) New information and ideas are filtered through people’s existing belief systems, cultural identities, and values. Thus, for some people the phrase “climate change” evokes ideas of environmentalists pushing a radical socialist agenda, distrust of scientists and the scientific process, more and bigger government tampering with the market, and even a challenge to their belief in God as master of the Earth. Others hear completely different connotations: the natural outcome of a consumerist market system run rampant, belief that scientific knowledge should guide modern decision-making, a much needed call for regulation to curb market excesses, and even the potential for breakdown of civilization as we know it if we fail to act.

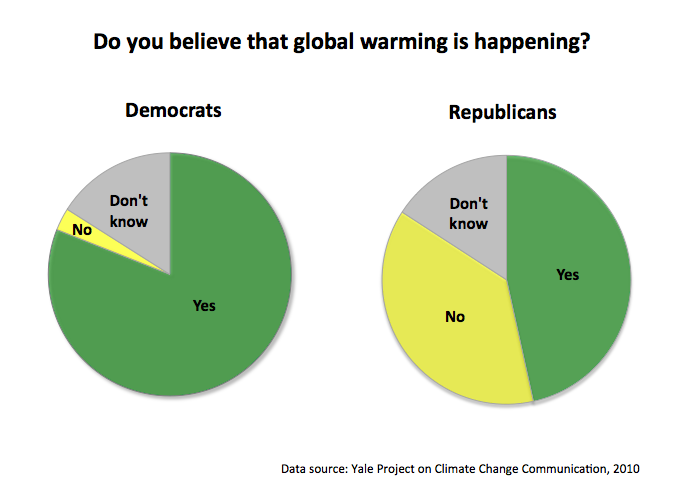

Understanding the role of culture and cognition in shaping public opinion on climate change is important because a connection between a position on the issue and one’s cultural identity is very hard to break. For example, multiple studies have shown that political party affiliation is the strongest correlate with belief in climate change.(d) This, to me, is the most visible sign of the cultural dimensions of the issue. Efforts to present ever increasing amounts of data, without attending to the deeper values that are threatened by the conclusions they lead to, will only yield greater resistance and make a social consensus even more elusive. Opposing sides are debating different issues, seeking only information that supports their position, disconfirms the opposing view, and demonizes the other side. Think of the news sources that people trust most to get a sense of the schism that is forming. Who do you trust more: Fox News or NPR; Al Gore or Rush Limbaugh? Each of these sources projects and represents different belief systems and worldviews, and thus different positions on climate change.(e)

The cultural logics that underlie each group of beliefs form the crux of the debate and, as opinions drift to more polarized extremes, develop into a dangerous schism. As the divide grows and extreme opinions dominate the conversation, discourse and the potential for compromise disintegrate.2 While one side sees the future of the planet at risk, the other sees freedom and economic growth being threatened. The two sides are not so much competing as they are talking past each other, and a functioning democracy is not possible under such circumstances.(f)

Breaking the Deadlock

There is hope, however. Decades of social science research as well as more recent work that connects that research to the climate change debate can help us wade through the vitriol and understand why climate change has joined sex, religion, and politics as topics you don’t mention in polite company without fear of a heated and divisive debate. For example, there is a large body of literature in dispute resolution and negotiations on how to engage in value-laden debates.3 This literature offers techniques for moving away from distributive win-lose configurations and towards “mixed motive” consensus-based discussions that are based on both the issue’s scientific and social dimensions.(g) Two examples valuable for the climate change debate are discussed below.4

Focus on broker frames. Effective advocates draw on the language and narratives of the group they are communicating with. Examples and frameworks that align with people’s existing worldviews can help them consider controversial issues in a new light. Categorizing climate change as primarily an environmental concern may only inspire action among people for whom this category is relevant, or worse, create resistance in those for whom this category is anathema. In response, advocates are increasingly using different broker frames to emphasize the economic, religious, psychological, sociological, developmental, and political implications of climate change. Potential broker frames include:

- U.S. economic competiveness. Secretary of Energy Steven Chu identified Chinese advances in clean energy technology as this generation’s “Sputnik moment”.

- National security. The elite retired officers who make up the Military Advisory Board at the non-profit research organization CNA categorized climate change a “threat multiplier“.

- Health and quality of life. A commission convened by top medical journal The Lancet called climate change “the biggest global health threat of the 21st century.”

- Social equity. Pope Benedict XVI framed climate change as an issue of respect for human dignity and for creation.

- Conservative values. Liberal think tank the Center for American Progress linked climate change with the high value placed on natural conservation by Republican Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Richard Nixon.(h)

Employ climate brokers. People are more open to arguments made by individuals they consider to be members of their cultural community. They often immediately discount and tune out claims from divisive figures, like Al Gore or Rush Limbaugh, who they view as being on the ‘other side’ of the partisan divide. The best climate brokers are individuals with credibility on both sides of the debate, particularly the right, since Republicans on the whole are more skeptical about climate change than Democrats. Politicians and pundits as well as advocates from the business world, the religious community, the entertainment industry, and the military can effectively reach audiences who may distrust anyone more closely associated with the left.

The Way Forward

It would be naïve to assume that a reconfiguration of the form of the conversation alone will yield a social consensus that climate change is real, that it is caused by humans, and that we should do something about it. Indeed, one major reason that climate change has become so culturally divisive in this country is because action threatens the interests of powerful economic and political groups. These groups have devoted substantial resources to challenging the validity of the scientific community and its research.

This political reality confounds the debate and creates obstacles to a social consensus, but it does not change the trajectory of the discussion nor the tactics to be employed. The weight of scientific evidence is massive and growing, though inevitably incomplete in explaining such a complex system. As Paul Edwards, author of A Vast Machine, explains, “The science of climate change is like a jigsaw puzzle with a few missing pieces. We don’t know everything, and real mysteries remain. But the overall pattern is clear and very unlikely to change dramatically, even if we find out that one or two of the pieces are out of place.” The current challenge on climate change is a social one: explaining the pattern that this complex jigsaw puzzle reveals to a skeptical public that is more concerned with the tangible and salient issues of a downturned economy, high unemployment, an uncertain retirement, and rising health care costs. Given the weight of these concerns, science alone will not compel people to act.

At the end of the day, climate change presents an existential challenge to our contemporary worldviews, and only by shifting those perspectives will we fully embrace the change that is necessary. It means accepting that we, as a species, have grown to such numbers, and our technology has grown to such power, that we can alter and manage the ecosystem on a planetary scale. This is an enormous cultural shift that alters our conception of the environment and the responsibilities that come from our newfound place within it. Yet it is a necessary shift if we are to develop the will to act on climate change.

Endnotes

- Dan M. Kahan, Hank Jenkins-Smith, and Donald Braman (2011) “Cultural cognition of scientific consensus,” Journal of Risk Research, 14(2): 147-174.

- Andrew J. Hoffman (2011) “Talking past each other? Cultural framing of skeptical and convinced logics in the climate change debate,” Organization & Environment, 24(1): 3-33.

- Kimberly A. Wade-Benzoni, Andrew J. Hoffman, Leigh L. Thompson, Don A. Moore, James J. Gillespie, and Max H. Bazerman (2002) “Barriers to resolution in ideologically based negotiations: The role of values and institutions,” Academy of Management Review, 27(1): 41-57.

- For more potential strategies see: Andrew Hoffman (2012) “Climate science as culture war,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, 10(4): 30-37.

Sidenotes

- (a) Limbaugh invoked high environmental taxes, old people dying in Britain from the cold, the insignificance of human behavior on the global environment and the divine plan of God (and creationism) in our inevitable emission of carbon dioxide as reasons why climate “models are all wrong.”

- (b) According to a study by the National Science Foundation, in 2010 the average American could only correctly answer 5.6 of 9 questions about basic issues in science and technology. Another national survey conducted by the California Academy of Sciences demonstrated even lower rates of scientific literacy among American adults, including the disturbing finding that only 53% of adults could correctly identify how long it takes the Earth to revolve around the sun.

- (c) The theory of cultural cognition posits that people’s perceptions of risk and their understanding of controversial topics are shaped less by facts and scientific evidence than by their ideological positions and cultural views. Facts are not rejected, but they are weighted and valued differently depending on each person’s pre-existing beliefs.

- (d) In 2010, on the cusp of the mid-term elections, a poll by the Yale University Project on Climate Change Communication found that 81% of self-identified Democrats believed global warming was taking place, compared to 47% of Republicans. The 2011 National Surveys on Energy and the Environment at the University of Michigan and Muhlenberg College found that 78% of Democrats, 47% of Republicans, and 55% of Independents believe there is solid evidence of the earth is getting warmer.

- (e) A 2012 study by the Union of Concerned Scientists found that “over a recent six-month period, Fox News Channel representations of climate science were misleading 93 percent of the time.” A 2010 Stanford University study found that “more exposure to Fox News was associated with more rejection of many mainstream scientists’ claims about global warming [and] less trust in scientists.”

- (f) Roger Pielke Jr., in his book The Honest Broker, describes the extreme of such schisms as “abortion politics,” where the two sides are debating completely different issues and “no amount of scientific information . . . can reconcile the different values.”

- (g) In game theory, a mixed motive situation is one in which the parties involved have at least some overlapping interests. This differs from a zero-sum game, in which one party’s gain always requires the other’s loss.

- (h) Though ‘environmentalist’ may not be the first word that comes to mind when people think of President Richard Nixon, he left a significant legacy of environmental protection, including the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and the signing of the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts.