In the second 2012 presidential town hall debate, undecided voter Lorraine Osorio asked the candidates, “What do you plan on doing with immigrants without their green cards that are currently living here as productive members of society?”(a)

Neither Barack Obama nor Mitt Romney volunteered a direct answer to the question of how to deal with the estimated 12 million undocumented immigrants in the United States. In their dodging and weaving, however, they demonstrated a better grasp of the complexities of public opinion about immigration than do many pollsters, who often reduce the issue to a binary of hostile versus welcoming sentiments.1 In reality, American opinions on immigration are complex and multifaceted.

One obvious reason why public opinion about immigration is complex is that the electorate is diverse. Both Obama and Romney are well aware that Latinos and other immigrants make up an increasing share of voters, including in swing states such as Florida, Nevada, and Colorado.(b) Nor can the presidential candidates overlook the swells of nativist backlash to these changing demographics, which have fueled harsh anti-illegal-immigration legislation like Arizona’s SB 1070 and Alabama’s HB 56.

However, American public opinion about immigration is complicated for another reason that is more fundamental than the opposing interests of immigrants and nativists. There is a divide in immigration attitudes within many voters’ own minds. Yes, there are some Americans in favor of closing the borders and deporting everyone without proper documents, and others who support open borders and citizenship for all regardless of their legal status. However, most Americans, regardless of national background, do not endorse either of these extremes. We could say that Americans tend to be moderate in their views on immigration but that would be uninformative, as “moderate” suggests a middle point along a single continuum between hostile and welcoming attitudes. Instead, Americans’ views on immigration occupy many points at once, because they are shaped by a patchwork of discourses.

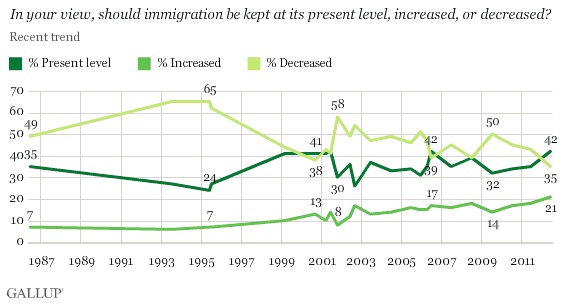

It is common for pollsters to probe American public opinion about immigration with the question, “In your view, should immigration be kept at its present level, increased, or decreased?” Gallup has regularly tracked answers to this question since 1986 and “decreased” outpolled or tied “present level” every year except 2000, 2006, and 2012, with “increased” lagging far behind either choice.2 These numbers seem to show high levels of unwelcoming attitudes toward immigrants, which might be attributed to nativism, racism (given that a large share of current immigrants are people of color), and scapegoating for economic troubles.3 Furthermore, after 9/11 the media began to link national security concerns to porous borders, which may account for the spike in the preference for decreased levels of immigration in 2002.

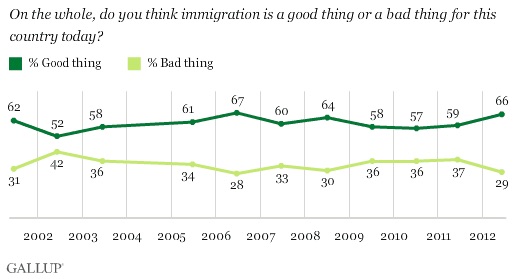

Now consider, however, responses to another question Gallup posed to the same respondents: “On the whole, do you think immigration is a good thing or a bad thing for this country today?” Since 2001, when Gallup began asking this question, “good thing” has consistently outpolled “bad thing” by wide margins. From these responses it appears that consistent majorities of Americans are supportive of immigration. How do we reconcile the seeming opposition to immigration in response to the first question with the seeming support for immigration voiced by the same people in response to the second question? In 2009 for example, half of those polled said immigration levels should be reduced but 58% of the same sample also said immigration is a good thing for the country.

To explain this pattern we need to abandon the idea that immigration attitudes – or attitudes on most topics of public concern – are shaped by broad, clearly defined ideologies or feelings. In my newly published book, Making Sense of Public Opinion: American Discourses about Immigration and Social Programs, I offer a different explanation.4 When an issue is a matter of frequent public discussion, people pick up the conventional discourses they hear around them, in what I call their opinion communities. Each conventional discourse is a simple mental schema that draws upon easily grasped ideas and often formulaic language. For example, Foreigners Taking Our Jobs is a common discourse that draws on ideas and language about immigrants “stealing” American jobs. On the other hand, the Culture of Diversity discourse emphasizes the cultural benefits (food, art, etc.) that come from America’s history as a “melting pot.”

Several conventional discourses may circulate within a given opinion community, and each person belongs to many such communities, ranging from face-to-face networks of colleagues and friends, to social media networks, to the audiences for national media and public figures. On issues that generate a fair amount of discussion, such as immigration, every adult is likely to have been exposed to a variety of conventional discourses. In Making Sense of Public Opinion I describe twenty such discourses about immigration that I heard voiced by average Americans during the course of my research interviews, as well as four more that were used by advocacy groups and politicians. Some discourses focused on negative aspects of immigration to America, some on positive aspects, while others were not easily characterized along a negative/positive continuum.(c)

People frequently hold multiple competing discourses on the same topic in their mind and may find validity in discourses that seem to conflict. The wording of one survey question could trigger one conventional discourse, while the wording of another question in the same survey triggers a different conventional discourse that seems at odds with the first. For example, when Gallup and other surveys ask, “In your view, should immigration be kept at its present level, increased, or decreased?” the wording focuses on the number of immigrants. The conventional discourse that most directly addresses immigration levels is Too Many Immigrants and its related negative discourses. Not everyone accepts the Too Many Immigrants discourse, but those who do would say immigration levels should be decreased. That was the predominant response among my interviewees when asked about immigration levels.

However, when I asked them for their thoughts about immigration in general, the very first thing many voiced was the Nation of Immigrants discourse, the idea of which, as my interviewee “Barbara Parks” put it, is that, “America is… the great melting pot.” The Nation of Immigrants discourse is personal; everyone except Native Americans recognizes that they are either immigrants or descended from them. It also portrays immigration as a source of strength in American history. The Nation of Immigrants discourse may be the major discourse evoked by the question, “On the whole, do you think immigration is a good thing or a bad thing for this country today?” which might be why responses to this question suggest a more positive view of immigration.

Politicians tend to be more calculating than the general public in their juxtaposition of competing discourses. Mitt Romney’s and Barack Obama’s initial responses to Lorraine Osorio’s question in the second presidential debate followed nearly the same script. Like my interviewees, both began with the Nation of Immigrants discourse:

Romney: [F]irst of all, this is a nation of immigrants. We welcome people coming to this country as immigrants. My dad was born in Mexico of American parents; Ann’s dad was born in Wales and is a first-generation American.

Obama: [W]e are a nation of immigrants. I mean we’re just a few miles away from Ellis Island. We all understand what this country has become because talent from all around the world wants to come here.

Next, Romney hinted at the Illegal is Wrong discourse, which draws a sharp line between welcoming legal immigrants and rejecting illegal immigrants.(d) He discussed streamlining the visa application system for highly skilled workers, then moved into an explicit Illegal is Wrong stance:

Romney: Number two, we’re going to have to stop illegal immigration. There are 4 million people who are waiting in line to get here legally. Those who’ve come here illegally take their place. So I will not grant amnesty to those who have come here illegally.

Obama likewise moved from a Nation of Immigrants discourse to an Illegal is Wrong discourse:

Obama: But we’re also a nation of laws. So what I’ve said is we need to fix a broken immigration system.

In a study of Congressional speeches about immigration legislation I found that the Nation of Immigrants and Illegal is Wrong discourses, along with the Land of Opportunity discourse and the National Security discourse, were the four discourses most evenly voiced by both immigration rights opponents and supporters.5 Obama and Romney also cleverly used other discourses that are hard to fit along a hostile/welcoming continuum, such as the Employers Taking Advantage discourse, which focuses on employers who hire illegal workers, rather than immigrants themselves:

Romney: I’ll put in place an employment verification system and make sure that employers that hire people who have come here illegally are sanctioned for doing so.

They also drew on the Speak English and Assimilate discourse, which frowns on immigrants who do not think or act as Americans but welcomes those who do:

Obama: [Y]oung people who come here… Ha[ve] gone to school here, pledged allegiance to the flag… Understand themselves as Americans in every way except having papers…we should make sure that we give them a pathway to citizenship.

Both Obama and Romney talked about streamlining the visa application system. This is not yet a common discourse among the public, but Streamline the Process is a conventional discourse in some policy-making opinion communities. The idea that we have to reduce the costs, complications, and delays of applying for a visa so potential workers can more easily immigrate legally is a good discourse for politicians unsure where their audience stands. It combines policies that would facilitate immigration with Illegal is Wrong rhetoric scolding immigrants who do not patiently wait in line.

Immigration attitudes in the United States are far more complicated than simply points along a continuum from welcoming pro-immigration to harsh anti-immigration views. The conventional immigration discourses that Barack Obama and Mitt Romney voiced during the second debate show that they and their political advisors understand this fact, perhaps better than some researchers and pollsters do. Whether their nuanced campaign statements will translate into meaningful immigration reform is another question.

This is the second in a series of articles by Dr. Strauss exploring topics from her new book, Making Sense of Public Opinion: American Discourses about Immigration and Social Programs. For an overview of the book, see her previous article for Footnote, “Beyond Left & Right: Exploring America’s Political Divide.”

Endnotes

- Some scholars have recognized that public opinion on immigration is not so simple. See, for example, Thomas J. Espenshade and Maryanne Belanger (1998) “Immigration and public opinion,” in Crossings: Mexican Immigration in Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Marcelo M. Suárez-Orozco, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, p. 365–403.

- Jeffrey M. Jones (2011) “Americans’ views on immigration holding steady,” Gallup online, June 22. In 2012, interestingly, only 35% of respondents said immigration should be decreased, the lowest level since 1965.

- For a summary of scholarly explanations of public opinion about immigration, see Joel S. Fetzer (2000) Public Attitudes Toward Immigration in the United States, France, and Germany, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Claudia Strauss (2012) Making Sense of Public Opinion: American Discourses about Immigration and Social Programs, New York: Cambridge University Press. For an overview of the general theoretical framework I propose in the book, see my earlier article for Footnote, “Beyond Left & Right: Exploring America’s Political Divide.”

- Claudia Strauss (2012) “How are language constructions constitutive? Strategic uses of conventional discourses about immigration,” Journal of International Relations and Development, August 3.

Sidenotes

- (a) Osorio is a 24-year old hairdresser from Long Island whose parents are from El Salvador. Her question was the most tweeted about moment from the second debate, in part because both candidates stumbled to pronounce her name correctly.

- (b) Latinos make up 11% of eligible U.S. voters, up from 8% in 2004. In the swing states of Nevada and Florida they account for more than 15% of eligible voters. However, turnout rates among Latinos who are eligible to vote have historically been significantly lower than among blacks and whites (50% compared to 65% and 66%, respectively, in the 2008 election).

- (c) An overview of some of the conventional discourses about immigration common in the U.S. is available here. Among the negative immigration discourses are Foreigners Taking Our Jobs, National Security, Help Our Own First, Illegal is Wrong, and an overarching Too Many Immigrants discourse linked to all of these. The positive discourses include Immigrants’ Work Ethic, Nation of Immigrants, and Cultural Diversity. Those that are not easily classified include Benefits for Contributors, Speak English and Assimilate, and Employers Taking Advantage.

- (d) According to the Pew Research Center, undocumented immigrants make up 4% of the U.S. population and 5.4% of the workforce.