From civil rights activist Malcolm X to Watergate conspirator Charles Colson,(a) jailhouse conversion has offered many a path from criminality to redemption. It is no surprise, then, that churches and faith-based non-profits(b) have played a critical role in the growing “prisoner reentry” movement,1 which seeks to better prepare people to reintegrate into society after incarceration. Reentry projects in the community are complemented by activities inside the prison walls, including comprehensive residential programs where participating inmates live in the same housing unit and spend their time involved in a range of religious and secular programming. The idea behind such residential programs is that participants benefit not only from discrete classes and activities but also from the overall experience of living in a positive environment with other inmates interested in self-transformation.(c)

In 2003, Florida became the first state in the country to dedicate an entire correctional facility to a faith-based model when it launched its first Faith- and Character-Based Institution (FCBI). The Florida Department of Corrections now operates four FCBIs housing a total of 3,300 inmates, all of whom volunteer for the program and most of whom spend between six months and a year and a half there. The FCBI model differs from many Christian prison programs in that it welcomes inmates and volunteers from all faiths(d) and offers a flexible curriculum consisting of classes and activities from a range of secular and religious perspectives. The diverse programs include explicitly religious activities, such as worship services and scriptural study; personal relationship building through mentoring and small group activities; and character development programs covering topics such as parenting and anger management; as well as the educational opportunities and vocational training found in all Florida prisons. All FCBI programming is designed, funded, and implemented by community volunteers, though few have professional expertise or training in correctional programming. Inmates choose which programs to attend and the FCBI experience is different for every participant: some simply fulfill the minimum requirement by attending one program session a week while others participate in multiple classes and activities each day.

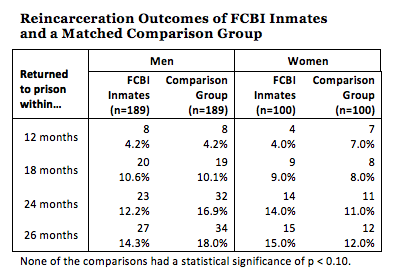

A 2008 study by Diana Brazzell and Nancy La Vigne of the Urban Institute found no statistical evidence that FCBI participation lowers recidivism(e) rates, despite strong anecdotal support for the program among inmates and correctional staff. Previous studies of other residential faith-based prison programs also failed to support the claim that they lead to better outcomes after release.2 Brazzell and La Vigne’s study focused on 189 men and 100 women who spent at least 3 months in an FCBI in 2004 and 2005. For each person in the FCBI group, they found a prisoner who matched that person’s gender, age, race, criminal history, and in-prison behavior record and who was incarcerated in a Florida state prison at the same time but was never in an FCBI. Analysis  roups would not have been detected statistically.

roups would not have been detected statistically.

Although statistical analysis showed no evidence of an effect on recidivism, correctional staff, facility management, program volunteers, and inmates expressed primarily positive opinions of the program during interviews. Staff and volunteers reported improvements in inmates’ attitudes and behavior and found the FCBI to be a safer, more pleasant working environment than traditional facilities. Inmates described the FCBIs as less dangerous and stressful and more conducive to self-improvement than other prisons. This strong anecdotal support for the FCBIs suggests that the model may hold promise despite its failure to reduce recidivism. The researchers suggest corrections officials and volunteers strengthen the program by providing thorough reentry services to extend any program benefits beyond the prison walls. They could refine the in-prison programming by incorporating evidence-based approaches that have been proven to reduce recidivism and involving volunteers with greater expertise and training.

Over the past decade, politicians(f) and religious leaders showed significant enthusiasm for faith-based programs and even those skeptical of religion saw promise in models that leverage untapped resources from the community – particularly motivated volunteers – at little cost to the state. Yet this study and others offer little firm evidence to support the effectiveness of comprehensive faith-based residential programs in prisons.3 While Florida’s FCBI initiative drew positive reviews from those involved and expanded the faith‐based prison approach to include different faiths, the model needs substantial refinement and further testing before it can demonstrate success.

Endnotes

- Dan Mears, Caterina Roman, Ashley Wolff, and Janeen Buck (2006) Faith-based efforts to improve prisoner reentry: Assessing the logic and evidence,” Journal of Criminal Justice 34: 351–367.

- Byron R Johnson and David B. Larson (2003) The InnerChange Freedom Initiative: A Preliminary Evaluation of a Faith-Based Prison Program, University of Pennsylvania, Center for Research on Religion and Urban Civil Society. Jeanette Hercik (2004) Rediscovering Compassion: An Evaluation of Kairos Horizon Communities in Prison, Caliber Associates. Neither study found lower recidivism rates among program participants compared to similar inmates from the general population and both had methodological limitations (small sample size, selection bias).

- Alexander Volokh (2011), Everything We Know About Faith-Based Prisons (working paper), Emory University Law and Economics Research Paper No. 11-99, Social Science Research Network.

Sidenotes

- (a) Shortly after converting to evangelical Christianity, Nixon aide Charles Colson served 7 months in federal prison for his involvement in the Watergate scandal. After release, he became an advocate for prison reform and founded the Prison Fellowship to provide a Christian-based approach to rehabilitation.

- (b) Blacks and Hispanics, who together make up 58% of prison inmates, are significantly more religious than the general US population.

- (c) A 2005 study found that 21 state correctional systems were operating or developing faith-based residential programs.

- (d) 11% of FCBI inmates practice a non-Christian religion (most commonly Islam or Judaism) and 12% do not identify as belonging to a particular religion. Volunteers are from secular groups and a range of religious traditions, although the vast majority are affiliated with Christian churches.

- (e) Recidivism, meaning a return to criminal activity, is a key indicator of the success of any program attempting to rehabilitate prisoners. Common measures include rearrest, reconviction, and reincarceration (the measure used in this study).

- (f) President George W. Bush was one of the most vocal proponents of faith-based programs, viewing their promotion as an essential part of his “compassionate conservative” legacy. His most important achievement in this area was creating the White House Office of Faith-based and Community Initiatives to increase government funding and partnership opportunities for faith-based organizations.