This article was produced as part of The Rhode Island College & University Research Collaborative, an innovative project to bring academic research and expertise to state policymakers.

In our increasingly technologically advanced and globalized economy, success requires adaptation to constant change. While “knowledge economy” sectors like tech and finance seem to have agility built into their DNA, older industries like manufacturing struggle to keep up.

How can manufacturing firms better adapt to the shifting landscape of today’s economy? Can trends like 3D printing and workforce automation offer greater agility? What will it take to cultivate a manufacturing sector that fits into the high-tech knowledge economy?

As educators engaged in the preparation of tomorrow’s workforce, we were interested in better understanding the future of the manufacturing sector and the role colleges and universities will play in it. We consulted a previously untapped source of expertise with a major stake in the conversation: the technical professional advisory boards associated with our home state of Rhode Island’s higher education institutions.(a) We surveyed 35 business leaders from these boards to gather their perspectives on the state’s economic outlook with respect to technology, innovation, and manufacturing.

The Rise and Fall of Manufacturing

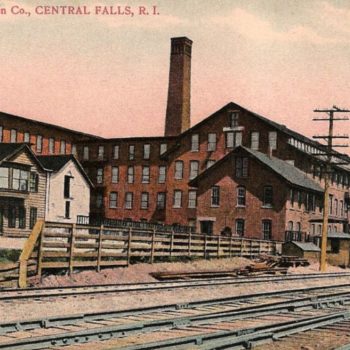

Rhode Island was once a major industrial hub and played a significant role in the American Industrial Revolution.(b) During the 18th century, for example, Nehemiah Dodge became the first “manufacturing jeweler” by producing a new form of plated gold and selling it to other goldsmiths. The jewelry industry thrived in Providence and became emblematic of the state’s economy. Since the industry’s decline, however, universities have expanded into now-abandoned factory buildings and Providence’s Jewelry District has transformed into the Knowledge District.

The evolution of Providence’s Jewelry District embodies larger changes within Rhode Island and the U.S.1 Although manufacturing productivity has increased, jobs have disappeared. Manufacturing now accounts for 7.7% of the state’s GDP, down from almost a third of GDP half a century ago.2 From 2000 to 2013, Rhode Island experienced the most dramatic manufacturing employment decline in the country, losing 44% of manufacturing jobs.

Much of the manufacturing sector’s decline is related to a fundamental shift in the U.S. from an industrial to an information and services economy.(c) The promise for manufacturing’s future may therefore lie in a sector more grounded in high-tech services and expertise.

Expert Perspectives on Manufacturing’s Future

To better understand these changes and where manufacturing could head in the future, we surveyed 35 business leaders from four college and university technical professional advisory boards.5 These leaders represent some of Rhode Island’s most prominent companies in manufacturing and related industries such as construction, engineering, and pharmaceuticals. We asked them a series of open-ended questions about the future of their companies and industries and the role of higher education institutions and of design and innovation in this future.

Our detailed analysis of the survey responses revealed four key themes regarding the needs of today’s manufacturing sector.6 These themes hint at ways that Rhode Island can revive manufacturing, promote innovation, and better prepare its workforce for the new economy.

1. Organizations should develop the flexibility to respond to changing market conditions.

Organizational flexibility and adaptability is critical for responding to today’s rapidly evolving technological and economic conditions. Companies need the capability, either in-house or through outsourcing, to engage in quick-turnaround activities to address new market trends or tailor products to consumer needs. Innovations such as rapid prototyping and 3D printing can offer companies the flexibility they need to address changing external conditions.

The business leaders we surveyed suggested that higher education institutions must also be agile. They have a responsibility to adapt training and educational opportunities to changing business environments and offer training in the technical skills currently in demand.

2. Innovation should be a core part of company culture.

In addition to being able to adapt to new developments coming from the market, companies also need to innovate from within. Most respondents report that innovation is a daily operating norm in their companies, with systems and practices in place to encourage and facilitate creative thinking. When seeking to foster innovation, the majority of companies look in-house first in order to protect the intellectual property of any resulting products. As major industry leaders, these businesses view their success as partly dependent on a corporate culture of continuous innovation and evolution that is embedded in the philosophy of everyday operations.

3. Workers should cultivate a broad range of skills.

As technology becomes more integrated and engineering systems and challenges more complex, students need a multidisciplinary education that builds a wide range of skills.(d) Many survey respondents emphasized the competitive advantage associated with educating globally and culturally aware “generalists” who are comfortable with a shifting technological and business landscape. Even technical workers need not only proficiency in areas like engineering or software coding, but also expertise relevant to international business – such as knowledge of a second or third language – and soft skills like communication, writing, and listening.

4. Leaders should develop alliances among education, industry, and government to build cohesive resource networks.

The business leaders we surveyed reported that Rhode Island has a rich inventory of resources for business development, training, and education, but said these resources are fragmented across a variety of locations and among many different sponsors and providers. Some respondents felt that the majority of resources are directed to the needs of startup companies and small businesses rather than large organizations working on cutting-edge engineering and technology challenges.

Enriching and integrating the resources available to businesses will require strengthening partnerships between higher education, industry, and government. This may entail the creation of new alliances or the expansion of existing collaborations such as internships and mentoring programs.

Building a Stronger Manufacturing Sector

How can Rhode Island and other states cultivate the four strengths identified by business leaders as essential for organizations, workers, and the manufacturing sector as a whole? One promising proposal would be to concentrate the many resources and capabilities in the state into a single entity. This alliance between higher education and industry would have the goal of improving and expanding Rhode Island’s manufacturing, engineering, and engineering services sectors.

A centrally located headquarters for the alliance could provide a place to assemble the many disparate services currently spread across institutions of higher education, state-supported agencies, and private organizations. Resources provided by the alliance might include a technology transfer office to transmit ideas from academia to industry, a business development office to connect investors and innovators seeking funding, an incubator space to help bring promising ideas to market, and a training space for cultivating worker skills.

As educators, we are acutely aware of the changing nature of our state’s economy and our duty to ensure our students are highly competitive and have access to promising employment opportunities. Our survey of business leaders produced valuable insight into how Rhode Island can strengthen its workforce and manufacturing sector to meet the needs of tomorrow’s economy.

With targeted initiatives addressing the needs of our state’s manufacturing firms, increased partnerships between academia, government, and the private sector, and ongoing guidance from Rhode Island’s current generation of business leaders, the state may be able to cultivate a generation of workers with the agility, adaptability, and worldliness to revive the manufacturing sector.

Endnotes

- Edinaldo Tebaldi (2014) “Manufacturing, Innovation, And Economic Growth: Challenges For Rhode Island And The Country,” Footnote, Feb. 7.

- National Association of Manufacturers (2012) “Rhode Island Manufacturing Facts,” Washington, DC: National Association of Manufacturers.

- This chart is based on historical data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Employment Statistics survey.

- These figures are based on data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages.

- We sent electronic surveys to all 51 individuals who serve on the Engineering and Construction Management Advisory Boards of Roger Williams University, the Chemical Engineering Advisory Board of the University of Rhode Island, and the Engineering Advisory Board of the New England Institute of Technology. We received responses from 35 individuals, a response rate of 69%.

- Our method for analyzing the extensive qualitative data collected through the surveys is outlined in detail in our full research report.

Sidenotes

- (a) Technical professional advisory boards provide input on the strategic direction of academic programs and serve as liaisons between higher education and the workplace. Many advisory board members are drawn from the executive-level management at some of the state’s largest employers.

- (b) Rhode Island’s industrial success was rooted not necessarily in inventing new technologies, but in adapting them rapidly.For example, Samuel Slater was the first in the country to adopt mill technology from England, building his famous Slater Mill in 1793 and launching the Industrial Revolution in New England.

- (c) While the manufacturing jobs remaining in the state are sometimes touted as well paying, Rhode Island ranks 39th in the country among states for weekly manufacturing wages, at $965. Our neighbors Connecticut and Massachusetts rank first and third respectively.4

- (d) According to the business leaders we surveyed, technical skills that are in high demand include: lean construction techniques, electro-mechanical expertise, and automation and process control.