This article was produced as part of The Rhode Island College & University Research Collaborative, an innovative project to bring academic research and expertise to state policymakers.

Every day, socially conscious shoppers are picking out the perfect apple at the farmers’ market or going a little out of their way to purchase a book at the mom-and-pop bookstore downtown. These consumers understand that handing over (sometimes a little extra) money to their neighbors offers valuable support to local businesses.

What some people may not understand, however, is that the $20 they spend on a novel contributes much more to the local economy than just the price of the book. Local vendors are more likely to spend that money at other local businesses and keep it circulating within the community. But while people and organizations are becoming more aware of this “multiplier effect” of local spending, small businesses still struggle to compete with large corporations that not only offer potentially lower prices, but also spend significant amounts of money on advertising and market research.(a) A small, local painting crew simply can’t compete with a national contractor when trying to win a contract at a major university. Or can it?

To address this question, we conducted research on the local purchasing practices of two large higher education institutions in Rhode Island: Brown University and Roger Williams University. We analyzed purchasing data and conducted interviews with university administrators to understand the obstacles and opportunities involved in buying from local vendors and identify strategies for promoting local purchasing. We also surveyed purchasing managers from prominent companies in Rhode Island.1

Our findings indicate that the purchasing decisions of major institutions like universities have the potential to make a significant impact on local economies, and that there are a number of promising ways to encourage local purchasing.

The Power of Local Purchasing

Over the past few decades, local businesses have faced competition both from “big box” stores like Target and Walmart and from the outsourcing of work to other countries, first in manufacturing and now for services such as data analysis and customer relations.(b) While big box stores can create jobs and outsourcing can provide cheap goods to retail outlets and consumers, both serve to increase profits primarily for large companies.2

Cultivating a strong local business sector, on the other hand, has numerous benefits for local economies and citizens.3 Money spent at local businesses stays in the local economy much longer, as local vendors are more likely to spend that money at other businesses in the community – for services such as accounting and advertising – than national chains that pay for these services through their corporate offices.4 In addition, local businesses are more likely to support their communities through charitable contributions and civic involvement.5

Small local businesses also provide economic resiliency and create jobs.6 Nationally, small businesses accounted for the majority of net job growth from 1990 to 2003, and, even during the recent recession, the number of jobs at small businesses remained steadier than at large firms.7 Large companies create jobs as well, of course, and sometimes with higher pay and benefits.8 Existing research does not suggest that states should halt efforts to attract large companies, but it demonstrates that small businesses rooted in the community can also have a substantial positive economic impact. Buying local is one way to support these businesses – and consequently the local economy – in the face of outsourcing, the growth of large corporations, and other economic challenges.

The Movement to “Buy Local”

The benefits of local purchasing are clear; the challenge is to convince buyers of these long-term benefits, particularly when purchasing from local vendors may entail somewhat higher price points and slightly more inconvenience in the short term. Fortunately, organizations and consumers are becoming more aware of the benefits of local purchasing. This is evident in the adoption of “buy local” campaigns, the development of local investment clubs, and the enormous growth of the local food movement.

Anchor institutions – large, locally based nonprofits such as universities, hospitals, sports venues, and cultural centers – can play an important role in promoting local purchasing. Because of their size and resources, these institutions have a significant impact on the local economy, serving as major employers and purchasers.(c) Anchor institutions also tend to be inextricably linked to their geographic locations, which gives them an incentive to invest in the community. The local spending practices of influential anchor institutions can also set the tone for the choices made by other organizations in a community.9

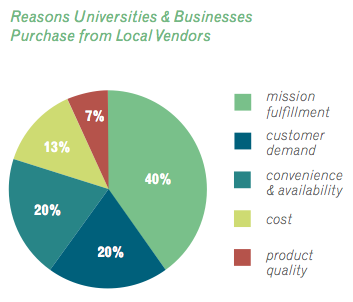

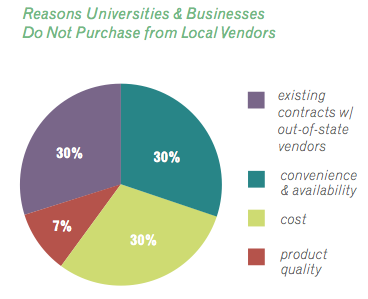

Why Organizations Do – and Don’t – Buy from Local Vendors

Our research examined local purchasing trends in Rhode Island. In our interviews and surveys, many universities and other organizations in the state reported that the benefits of purchasing locally include higher-quality products and quicker delivery. For example, many food purchasers spoke not only of the superior quality of the produce but also of the reduced environmental footprint created by buying local food. Local purchasing also helps organizations improve their image, maintain consistency with mission statements related to community development, and fulfill affirmative action policies that focus on small minority- and women-owned businesses.

Despite the recognition of these benefits by universities and other organizations, local purchasing appears to be less common in Rhode Island than in some other states, likely due to our relatively small size. Many organizations we interviewed and surveyed consider purchases in Massachusetts and Connecticut to be “local” (although we only included purchases from Rhode Island vendors in our study). Other obstacles to local purchasing include higher price points for local goods and limitations in existing contracts with large distributors that bulk purchase goods and rarely source local products.

Local Purchasing by Rhode Island Universities

To understand the purchasing activity of higher education institutions, we obtained and analyzed 2013 purchasing data from Brown University and Roger Williams University. The data do not cover all local purchases by the two universities (for example, spending by individual academic departments is not included), but still show a significant amount of money is being spent with local vendors. Annual local purchasing by Roger Williams totaled $9.7 million in 2013. In the seven months from July 2013 to January 2014, Brown University spent $36.7 million at local businesses, including $3 million on locally sourced food. For comparison, Brown’s operating budget for 2013 was $865 million.

The main sectors where Roger Williams and Brown made local purchases were construction, food, and the service sector, including trade services (i.e. clerical work, trash removal, etc.) and program services (professional services related to the universities’ teaching and research programs). These trends support the argument made by some experts that services and non-durable goods are the low-hanging fruit to focus on when establishing local purchasing policies and initiatives.4

We measured the impact of the universities’ local purchasing on Rhode Island’s economy using a local economic multiplier, which is intended to capture the way that money is spent and re-spent within a community.(d) The multiplier estimates that for every $1 of local spending by higher education institutions, $1.94 recirculates in the Rhode Island economy. (For comparison, multipliers for other kinds of spending in various regions of the country range from $1.20 to $3.07.) Based on this estimate, the $46.4 million in local purchasing we documented at just two universities induces an additional $43.6 million in other areas of the state’s economy, resulting in a net total economic contribution of $90 million.

Encouraging Local Purchasing

There are a number of policies and programs that might increase local purchasing. As our research demonstrates, universities and other large organizations spend significant amounts of money that could be channeled into the local economy. Higher education institutions, hospitals, large nonprofits, and state and local government agencies can revise their procurement policies to track spending with local vendors and give preferences to qualified local businesses.(e) Efforts to increase local purchasing by major government and nonprofit institutions could focus on the areas where barriers to local purchasing are already low, such as construction, food, and business services.

Government and nonprofit organizations can also work to remove existing barriers to local purchasing, such as the low public profile of local vendors and the complex bureaucratic requirements that often surround contracting. Brown University, for example, has made targeted efforts to increase opportunities for local vendors, with a specific focus on minority- and women-owned businesses. The university worked with the state to host events linking Brown’s major contactors to small, local trades companies. They also held information sessions for small businesses on how to meet Brown’s licensing and insurance requirements.

Another solution is the implementation of “buy local” campaigns that raise awareness about the benefits of local purchasing and encourage consumers and organizations to purchase from businesses in their communities. Research suggests that, in 2012, local businesses in cities with “buy local” campaigns saw double the revenue growth of businesses in cities without such campaigns.10

Multiplying the Power of Buying Local

One of the companies benefitting from Brown’s outreach to local vendors is Heroica’s Painting, a minority-owned family business that has been awarded 12 direct contracts with the university’s facilities management department since 2009. Heroica’s, in turn, gives back to the community by donating to a local nonprofit that trains minority youth in the construction business. This pay-it-forward chain of benefits embodies the multiplier effect of buying local and shows how targeted efforts to encourage local purchasing can benefit a number of stakeholders, from purchasers and vendors to the broader community.

Given the economic and civic benefits of a strong local business sector, it is certainly worth exploring opportunities to increase local purchasing. For decades, tax breaks and other incentives have been used to attract large national corporations; initiatives encouraging local purchasing might also offer a way to drive growth from within a state. Organizations and consumers should also understand how choices about where money is spent can influence their state’s economic and civic strength. By supporting other local businesses, creating resiliency in times of economic hardship, and promoting civic development, strong local businesses ultimately benefit the entire community.

Endnotes

- We also obtained purchasing data from Providence College, but it did not contain sufficient detail to be used in our analysis. The six university administrators we interviewed included purchasing managers, an assistant vice president, and a director of state and community relations. We also surveyed 18 purchasing managers from companies that are among the top employers in Rhode Island.

- Alessandro Bonanno and Stephen J Goetz (2012) “WalMart and Local Economic Development: A Survey,” Economic Development Quarterly, 26(4): 285-297.

- Kelly Edmiston (2007) “The role of small and large businesses in economic development, Economic Review, 2: 73-97. Jed Kolko and David Neumark (2010) Does local business ownership insulate cities from economic shocks? Journal of Urban Economics, 67(1): 103-115. Edward Glaeser and William Kerr (2010) The Secret to Job Growth: Think Small, Harvard Business Review, 88: 26.

- Michael Shuman (2012) Local dollars, local sense: How to shift your money from Wall Street to Main Street and achieve real prosperity, Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Stacy Mitchell (2003) “The Economic Impact of Locally Owned Businesses vs. Chains: A Case Study of Midcoast Maine,” Washington, DC: Institute for Local Self Reliance. Thomas A. Lyson, Michael D. Irwin, Charles M. Tolbert, and Alfred R. Nucci (2001) Civic community in small‐town America: How civic welfare is influenced by local capitalism and civic engagement, Rural Sociology, 67(1): 90-113. Stephan J. Goetz and Anil Rupasingha (2006) Wal-Mart and social capital, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 88(5): 1304-1310. Lyson et al. 2001.

- Glaeser and Kerr 2010.

- Edmiston 2007. Koko and Neumark 2010. Brian Headd (2010) “An Analysis of Small Business and Jobs,” Washington, DC: U.S. Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy.

- Edmiston 2007. Headd 2010.

- Econsult (2014) Survey of the Current and Potential Impact of Local Procurement by Philadelphia Anchor Institutions, Report Prepared for the Philadelphia Office of the Controller.

- Mitchell 2003.

Sidenotes

- (a) The term multiplier effect refers to the phenomenon whereby one dollar of spending can have more than a dollar’s worth of impact on an economy. The person or business receiving the dollar will spend it on something else, creating income for another person or business, who will then spend it again, and so on. The continuing circulation of the initial dollar creates a ripple of economic value.

- (b) Big box stores, named after their massive size and box-like appearance, typically sell a variety of low-priced goods at large volumes.

- (c) A third of Rhode Island’s top employers are hospitals or universities.

- (d) Economists develop multipliers for specific geographic areas and types of spending based on how quickly various kinds of spending flow out of local economies. Economic impact studies like ours can then use these multipliers to determine the impact of specific categories of spending.

- (e) The 2014 Rhode Island Food Bid, which seeks distributors for all food consumed in state institutions such as schools, added a “buy local” provision requiring distributors to compile a list of local food vendors and make efforts to purchase from these vendors. The request for proposals also allows for perishable and non-perishable foods to be separated into different contracts, potentially making it easier for local companies, which often specialize in produce and other perishable foods, to compete.