This article was produced as part of The Rhode Island College & University Research Collaborative, an innovative project to bring academic research and expertise to state policymakers.

Over the past decade, pundits have been lamenting the decline of American manufacturing and debating how to reinvigorate industry. At the same time, the rise of the so-called knowledge economy(a) has put the spotlight on the critical role that knowledge and innovation play in fueling job and wealth creation and promoting sustainable economic growth.1

The new knowledge economy is characterized by a significant increase in the contribution of service sectors, including information technology, education, science, technology, and finance, to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and employment.2 As the knowledge economy has grown over the past three decades, the contribution of manufacturing to the GDP and total employment has significantly declined.

The state of Rhode Island, for example, was hit particularly hard. According to my analysis of data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, it led the country in manufacturing job loss from January 2000 to January 2013, with 44% of manufacturing jobs in the state evaporating over that period. The United States as a whole experienced a 31% decline in the number of manufacturing jobs during the same period.

Can the U.S. – and hard-hit states like Rhode Island – revitalize manufacturing?

The Rise and Fall of Manufacturing

The Industrial Revolution marked the rise of manufacturing and radically improved production methods, leading to an era of economic progress and development never experienced before on the planet. The spread of manufacturing and mass production created the conditions for a significant increase in living standards for ordinary people.3

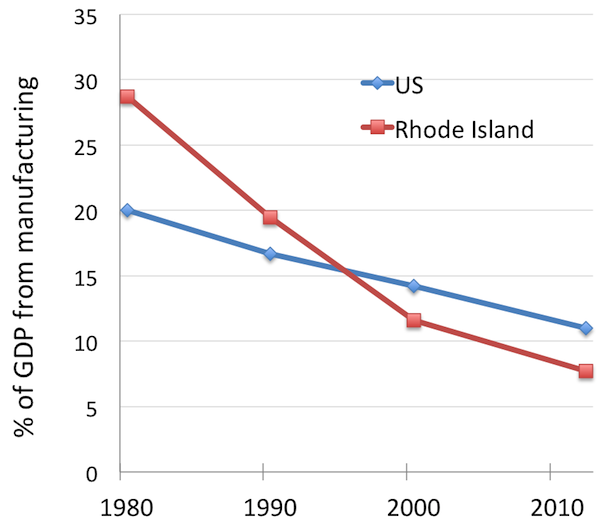

History shows that Rhode Island was an important player during the Industrial Revolution, and its economy benefitted accordingly. In the late 18th century, the state was at the frontier of advanced manufacturing and reaped the benefits of innovation and technological progress that took place across the region. The Blackstone River Valley in Rhode Island and Massachusetts is known as the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution in America. Businessman Samuel Slater of Pawtucket, who created technologies and a business model adopted by textile mills across New England, is often called the father of American industry. Slater’s mills significantly contributed to the creation of wealth, jobs, and economic development across the region.(b)Fast-forwarding to the early 1960s, manufacturing activity was still a major engine of both job and wealth creation. According to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, manufacturing accounted for about 30% of the GDP in Rhode Island and 29% of the U.S. GDP. However, in the 1970s and early 1980s, technological change, together with market forces such as global competition and production reorganization, caused a major structural shift. The U.S. transitioned from an economy intensely focused on manufacturing to a service-oriented economy, redefining the role of manufacturing in Rhode Island and the rest of the country.4 This shift has caused many to fear that there is no future for U.S. manufacturing because of America’s higher labor costs, stringent labor standards, and strict regulations.

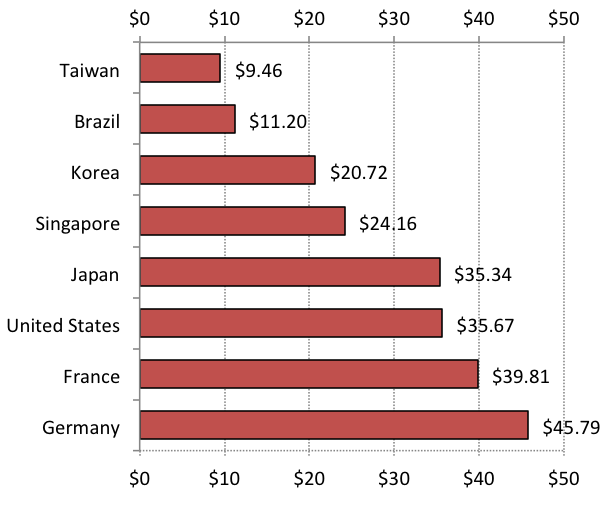

In this new landscape, competition in national and global markets for manufactured goods has been fierce and has caused a relocation of production to places where labor and transportation costs are lower (see figure below) and where the overall business environment is conducive to manufacturing activity.(c) The consolidation of traditional industrial powerhouses like Japan and Germany, together with the rise of mega industrial centers in China, Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan, changed the manufacturing marketplace.5 The effect was particularly pronounced in Rhode Island: Economists from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that Providence was one of the cities most vulnerable to competition from low-wage Chinese manufacturing between 1990 and 2007.

As a result of these changes, the proportion of the state and national GDP derived from manufacturing declined significantly over the past three decades. Manufacturing now accounts for 7.7% of Rhode Island’s GDP, compared to nearly a third of the state’s GDP half a century ago. The impact on manufacturing employment was even greater. In Rhode Island, employment in manufacturing declined by two-thirds, from 124,000 jobs in the early 1980s to about 40,000 jobs in 2012. In the United States as a whole, employment in manufacturing dropped about a third from 19.2 million jobs to 12.1 million jobs in 2012, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The Promise of Productivity

The role of manufacturing in Rhode Island’s economy, as well as the nation’s, has undeniably diminished over the past several decades. Could this decline have been avoided? More importantly, can it be reversed?

The truth is that the bleak figures about job loss and declining share of GDP tell only half the story. The good news from the manufacturing sector over the last few decades is a steady increase in productivity, that is, in the amount of economic value produced for a given amount of inputs.7 Because productivity growth – the ability to do more with less – is the engine of long-term economic expansion, manufacturing continues to be an important driver of growth in the United States.1 Productivity in manufacturing has also been increasing at a faster pace than in other sectors of the economy. From 1987 to 2007, productivity grew, on average, 3.7% per year in manufacturing compared to 2.3% in other (non-farm) business sectors.8

Productivity growth could give U.S. manufacturing an advantage over international competitors.(d) While other countries may have lower labor costs, America’s capabilities in product development and innovation can offer a competitive edge through the development of labor-saving technologies. But while productivity growth may increase manufacturing revenue and worker compensation, the creation of new jobs is unlikely to proceed at the same pace. Productivity gains and labor-saving technologies like industrial robots create wealth by producing more bang for a buck, but don’t necessarily require hiring more workers. Manufacturing will, however, contribute to job creation via its indirect impact on other sectors of the economy, particularly service sectors that create the human capital (education), research, and innovation to drive manufacturing productivity.(e)

The Path Forward

There is a great deal that leaders at the national level and in states like Rhode Island can do to promote productivity growth and innovation in manufacturing. Promising efforts include education and training to facilitate human capital development, support for research and development across the economy, and regulations and reforms that improve the local business climate.9 As leaders determine which policies and programs to pursue, they must weigh multiple, sometimes competing goals. Is the aim to create more blue-collar jobs or foster high tech and professional jobs that support advanced manufacturing? Is increasing wealth (GDP) and growing the manufacturing sector valuable even if it does not produce new jobs?

It is up to policymakers, business leaders, and the community to decide what the priorities should be for government-led efforts to revitalize manufacturing. But when it comes to determining what specific policies to implement and anticipating how they will work, academics have a great deal to offer.(f) Extensive economic research exists on the impact of policies and programs designed to foster manufacturing in different economic climates. By examining what strategies have succeeded in other states and countries, policymakers can better understand how to reinvigorate the manufacturing sector.

Endnotes

- Paul Romer (1990) “Endogenous technological change,” Journal of Political Economy, 98: S71-S102. Robert Lucas (1988) “On the Mechanics of Economic Development,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1): 3-42. Edinaldo Tebaldi and Bruce Elmslie (2008) “Institutions, innovation and economic growth,” Journal of Economic Development, 33(2): 1-27.

- Walter W. Powell and Kaisa Snellman (2004) “The Knowledge Economy,” Annual Review of Sociology, 30: 199-220.

- Lucas 1988.

- Lindsey Wilson (2013) “Manufacturing Concentration across the United States,” Manuscript, Bryant University.

- Wilson 2013. Susan Houseman, Christopher Kurz, Paul Lengermann, and Benjamin Mandel (2011) Offshoring Bias in U.S. Manufacturing, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(2): 111-32. Gary P. Pisano and Willy C. Shih (2012) Producing prosperity: Why America needs a manufacturing renaissance. Cambridge, M.A. and London: Harvard University Press.

- Joseph A. Schumpeter (1950) Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, New York: Harper & Row.

- Houseman et al. 2011.

- The productivity data are from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS); they do not provide productivity data at the state level.

- Pisano & Shih 2012.

Sidenotes

- (a) Stanford sociologists Walter W. Powell and Kaisa Snellman define the knowledge economy as one with “a greater reliance on intellectual capabilities than on physical inputs or natural resources.”2 Sectors such as scientific research, telecommunications, web technology, and finance depend on “knowledge-intensive activities that contribute to an accelerated pace of technical and scientific advance.”

- (b) Slater built the “first successful water-powered textile mill” in Pawtucket in 1793. His factory management model, known as the Rhode Island System, involved the creation of mill towns where life centered on local factories.

- (c) Competition and reorganization of production are not inherently destructive. Economist Joseph A. Schumpeter explained that competition and production cycles force markets to “periodically reshape the existing structure of industry by introducing new methods of production.”6 This process of creative destruction, while temporarily painful for many, serves as a fundamental engine that drives capitalism forward and creates prosperity.

- (d) While the U.S. was outperformed in manufacturing productivity (measured as output per hour of labor) by Korea and Taiwan over the past few decades, productivity growth in the U.S. has been faster than in other industrial powerhouses like Japan, France, Germany, and Canada. It is also important to note that productivity growth in countries like Singapore, Korea, and Taiwan may slow now that these economies have matured past an initial stage of rapid growth.

- (e) Regional multiplier data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis imply that, on average, for each manufacturing job created in Rhode Island, two jobs are created in other sectors of the state's economy.

- (f) In Rhode Island, academic experts are sharing this research with policymakers through the RI College & University Research Collaborative. The Collaborative is a public/private partnership that brings together scholars and policy leaders to incorporate more academic evidence and expertise into the policymaking process.