Epidemics do not spring forth fully formed; they gestate in pockets of disease that fester, spreading their tendrils further and further outwards. Amidst the violence of the current crisis in Syria, an epidemic of sexual assault has taken shape.

Ongoing reports of sexual torture, gang rape, and pervasive abuses have added Syria to the list of countries where sexual violence has been used as a weapon of war.(a) While Syria once boasted a reputation as a country where women enjoyed a relatively high level of security in the streets, these days simply leaving one’s home to attend school or buy bread carries the risk of attack. The epidemic of rape is not simply an offspring of the current crisis, however; Syrians have lived with state-sponsored sexual violence and torture for decades. And in a culturally conservative country, the threat of sexual degradation serves as a particularly potent weapon.

Sexual violence has emerged as an issue in other countries transformed by the Arab Spring. In 2011 allegations surfaced of mass rape perpetrated by Muammar al-Gaddafi’s troops in Libya, including claims that Gaddafi ordered the distribution of Viagra-like drugs to his troops to enable them to rape more effectively. (These allegations, it should be noted, have never been substantiated by independent investigators.) During the uprising against Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, numerous women were sexually assaulted in Tahrir Square. Perhaps the most publicized attack was on UK journalist Lara Logan, who was assaulted by between 200 and 300 men while reporting from the square.(b) But nowhere has rape become such a stable and normalized feature of an Arab Spring conflict as it has in Syria.

According to a report recently published by Women Under Siege, a project of the Women’s Media Center that gathers data on sexual violence in conflict zones, rape has become a systematic element of the Syrian conflict.1 By their estimates, the majority of cases involve female victims, but at least 20% of the victims of rape in Syria are men. Data on sexual violence is notoriously hard to gather, however, particularly in relatively conservative cultures like Syria that consider rape a shame on the victim.(c) Women Under Siege’s Lauren Wolfe continually reminds the public that the numbers her organization publishes are not only impossible to verify – given the extent to which access to Syria has been restricted by the government – but also incomplete, especially when it comes to men. Almost no one questions that there are far more incidents of sexual violence than have been reported, committed by both opposition and regime forces.

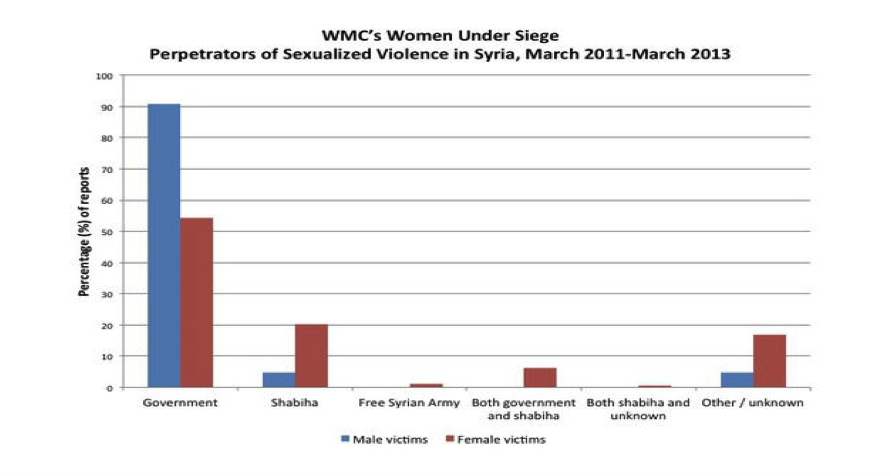

The statistics that WMC’s Women Under Siege has been able to gather show that, while both sides of the conflict have committed atrocities, over 80% of the perpetrators of sexual violence against women and over 90% of the perpetrators against men are government or government-affiliated forces (either regular units or shabiha security forces).(d) In an interview with Foreign Policy, Wolfe noted that, while the statistics may be skewed by the vigilance shown by anti-government protestors in documenting abuses, they may also simply reflect the truth on the ground. According to a special report on sexual violence in war published by the United States Institute of Peace, “Armed state actors are far more likely than rebel groups to be reported as perpetrators of rape and other sexual violence,” possibly because opposition groups often rely on the goodwill of the population for material support.2

While it is clear that the current conflict has spawned rape and sexual violence, Syrians have lived with the threat of institutionalized sexual assault for decades. Both women and men have long known that being detained by security forces entailed a risk of sexual violence, including but not limited to rape and sodomy. Behind the high walls and barbed wire of detention centers one might be stripped and paraded in front of security forces or have electric shocks administered to the genitals, as well as being sodomized by groups and individuals, or raped by force and violent coercion. Certain prisons, particularly military prisons, have long been notorious for the prevalence of sexual violence.(e)

Mahmoud, a young Syrian Shia from Damascus with bright blue eyes who worked in the souq (market), spent years dodging military service until eventually the military police caught up with him. When they told him that he was going to be sent to Tadmur military prison as punishment, he began making plans to commit suicide. “I wasn’t going to Tadmur,” he told me several years ago, before the current conflict began. “You don’t come out of Tadmur a man. They put people in a truck for Tadmur, and by the time they arrive someone has killed themselves. I could not survive.” The only reason he is alive, he says, is that as he was preparing to kill himself the night before his transport left for prison, the Syrian President issued a pardon.(f)

As the conflict in Syria has escalated, sexual violence has crawled out of the dark, secret cellars of regime detention facilities and become a feature of daily life. Videos posted online purport to show young women being grabbed off the street and taken into trailers and alleys where they are gang-raped. Women Under Siege1, the International Federation for Human Rights3, Human Rights Watch4, and others have received reports of women and men being raped in detention facilities, on the streets, and in their homes, sometimes in front of their families. Some victims are killed so they cannot identify their attackers, while others are left alive to suffer the aftermath of the attacks.

The aftermath is significant for both women and men.5 In Syria, as in a broad range of countries, a woman’s body is the site of her honor. She and her family are expected to guard her bodily integrity, so rape and other violations carry significant social stigma and shame.3 Women who have been attacked outside the view of witnesses may lie in order to hide what happened, in the hope that they can one day build a life not dominated and defined by the assault. There have even been reports of men preemptively divorcing their wives when it is learned that the women have been taken by security forces, in order to avoid any shame from sexual assaults they may be subjected to while in custody.

Some women who have been raped and then managed to flee Syria report wishing they had died, since they can no longer expect to have a husband and children or be anything other than a burden of shame on their families. Women subjected to extreme forms of sexual violence and torture can become incapable of having children, dooming them to an isolated and impoverished life in a culture where a woman’s worth is often directly tied to her fertility.(g) Those who do become pregnant fear becoming the victims of honor killings or, if they live, seeing their children face a life of hardship.4

These are the reasons why sexual violence is not simply another tool of war, but perhaps the ultimate weapon, particularly in a sexually conservative country. Murder and executions function by destroying an opponent, but they leave behind people who are ready and willing to pursue vengeance. Sexual violence, on the other hand, may not kill its victims, but it leaves them and their families broken, the trauma resonating outward as it shatters family structures and ravages the minds of survivors.(h) One can kill the men who take up arms against the regime, or one can sodomize them and sexually abuse them until they are rendered ‘feminized,’ passive victims drained of the masculinity that is often seen as a necessary element of being a soldier.3 And by violating a woman’s body, the ‘womb’ of the new country or nation that one is fighting against, one destroys the potential nation that she stands for.

Feminist scholar Catherine McKinnon described the rape camps of Bosnia as follows: “It is rape as an instrument of forced exile, to make you leave your home and never come back. It is rape to be seen and heard by others, rape as spectacle. It is rape to shatter a people, to drive a wedge through a community.”6 While the full scope of sexual violence in Syria will not be fully known until the conflict ends, its purpose is clear: to destroy the opponent in one of the most damaging and traumatic ways possible.

This article is part of a series turning an academic lens on current social, political, and economic events in Syria.

Endnotes

- Lauren Wolfe (2013) “Syria Has A Massive Rape Crisis,” Washington, DC: Women’s Media Center. The widespread sexual violence in the Syrian conflict has also been documented by the International Federation for Human Rights (see endnote 3), Human Rights Watch (see endnote 4), and other NGOs and media outlets.

- Dara Kay Cohen, Amelia Hoover Green, and Elisabeth Jean Wood (2013) “Wartime Sexual Violence: Misconceptions, Implications, and Ways Forward,” Washington, DC: United States Institute For Peace.

- Jeanne Sulzer (2013) “Violence Against Women in Syria: Breaking the Silence,” Paris: International Federation for Human Rights.

- Human Rights Watch (2012) “Syria: Sexual Assault in Detention,” Human Rights Watch online.

- Cassandra Clifford (2008) “Rape as a Weapon of War and its Long-term Effects on Victims and Society,” presented at the Seventh Global Conference on Violence and the Contexts of Hostility in Budapest on May 7th.

- Catherine MacKinnon (1993) “Crimes of War, Crimes of Peace,” in On Human Rights: The Oxford Amnesty Lectures 1993, edited by Stephen Shute and Susan Hurley, New York: Basic Books, p. 89.

Sidenotes

- (a) Places where sexual violence has recently been an instrumental strategy of waging war include Bosnia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Chechnya, and the Sudan.

- (b) Sexual violence has continued to rear its head during the recent protests in Egypt, with more than 100 reports of sexual assault in the area around Tahrir Square during the first week of July.

- (c) In an effort to overcome the obstacles to gathering data about sexual violence in Syria, WMC’s Women Under Siege has mounted an innovative effort to crowdsource data. Their website provides an online map of reported incidents of sexual violence, along with first-person and witness testimony, and allows victims and witnesses to directly report incidents for inclusion in the database.

- (d) The shabiha are informal security forces made up primarily of Alawites loyal to the Assad regime. They have been accused of carrying out some of the most brutal acts of violence since the beginnings of the conflict.

- (e) The Tadmur and Latakia prisons and the “Palestine Branch” of Military Security in Damascus have been particularly notorious sites of physical and sexual torture.

- (f) Mahmoud, who requested his real name not be used in this article, is currently living in Europe. As of June 2013, he was considering returning to Syria to fight on the side of the government. Like Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and his regime, Mahmoud is an adherent of Shia Islam; many members of the opposition are Sunni Muslims.

- (g) One common result of violent rape or sexual torture is obstetric fistula, a condition in which a hole develops between the rectum and the vagina. Women who suffer from fistulas often cannot carry children to term or control their bodily discharges. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, numerous women have been diagnosed with traumatic fistulas as a result of the sexual violence endemic to the conflict there.

- (h) Sexual violence has only recently been recognized as a crime against humanity. While the 1949 Geneva Convention prohibited wartime rape and forced prostitution, it was not until 1993, as reports of the rape/death camps in Bosnia emerged, that rape was defined at the Vienna Convention as a crime against humanity. 1996 marked the first time that officials responsible for mass rape were charged with crimes against humanity, stemming from assaults that took place in Bosnia. It was not until 2013 that the G8, the group of the most economically and militarily powerful nations in the world, recognized rape as a war crime.