This article was produced as part of The College & University Research Collaborative, an innovative project to bring academic research and expertise to Rhode Island policymakers.

As our economy develops over time, the demand for different kinds of work rises and falls. Farming gave way to manufacturing, which in turn has been eclipsed by knowledge and service jobs. Unfortunately, workers often have a hard time keeping pace with these changes. A factory worker laid off during the Great Recession, for instance, may not have the skills or experience to jump into a growing industry like education or health care. When entire categories of workers are displaced from declining industries and find themselves unable to transition into growing industries, workers are said to be “mismatched” with available jobs.

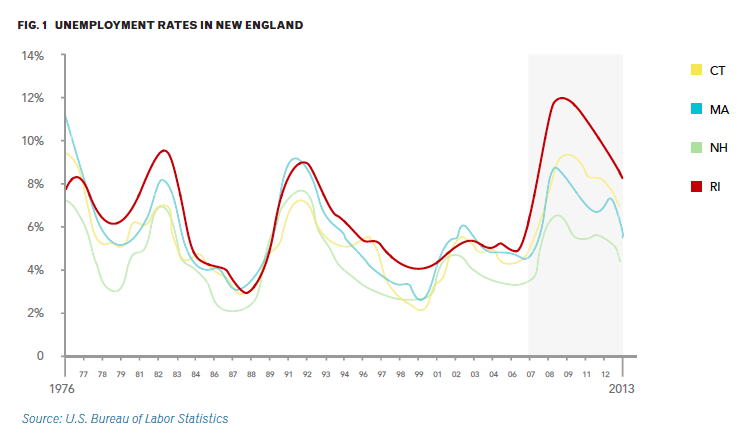

Economists and policymakers have voiced concerns that labor market mismatch (sometimes called structural unemployment) contributed to the high levels of unemployment experienced in the U.S. since the Great Recession.(a) What role has mismatch played in Rhode Island, which has had one of the highest unemployment rates in the country in recent years? My analysis indicates that, while labor market mismatch may play a part, it does not appear to be the dominant factor explaining why Rhode Island’s unemployment rate has been so much higher than the rest of the country.

Labor Market Mismatch and the Great Recession

Labor market mismatch refers to situations in which unemployed workers searching for jobs cannot connect with available job openings. Mismatch can occur when workers lack the right industry experience or educational skills to fill available jobs. A former metalworker, for example, cannot simply walk into a hospital and get a job as a nurse. It can also take the form of geographical mismatch, where open jobs and willing workers are located in different regions.

Shifts in the industrial or geographical distribution of jobs can lead to labor market mismatch when workers cannot adapt to these changes. Mismatch results in a higher unemployment rate as available jobs remain unfilled because, even though there are available workers, they are not the right fit for the jobs.

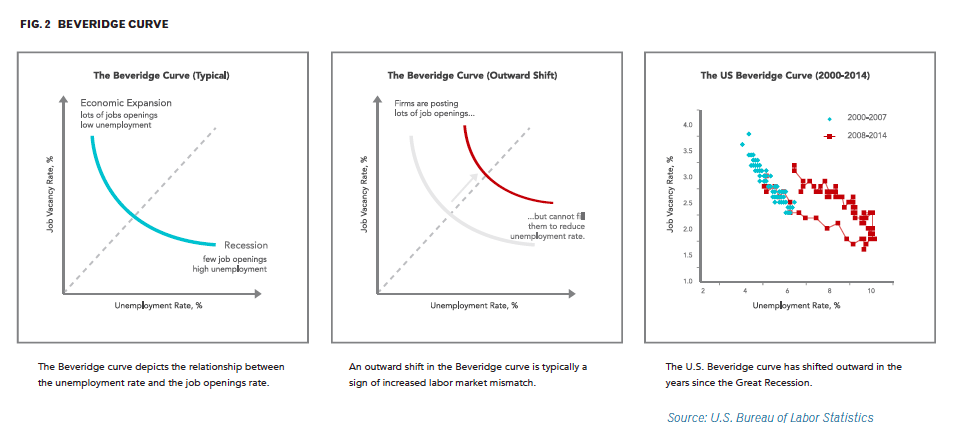

One of the main ways to visualize the match between workers and jobs is the Beveridge curve, which depicts the relationship between the unemployment rate and the job openings rate (the typical U.S. Beveridge curve is shown in blue in Figure 2).1 During periods of economic expansion, the economy is at the top left side of the curve, as more jobs are opening up and unemployment is low. Recessions involve movement to the lower right part of the curve, as job openings fall and the unemployment rate rises.

Since the end of the Great Recession in 2009, the Beveridge curve appears to have shifted outward, which is typically a sign of increased labor market mismatch (the post-recession Beveridge curve is shown in red in Figure 2). Job openings started rising after the end of the recession, but without the corresponding decline in unemployment we would typically expect. In essence, firms started posting more open positions but did not quickly hire workers and reduce the unemployment rate, possibly because unemployed workers weren’t a fit for these jobs.

Despite the shifts in the Beveridge curve, there remains debate about how much labor market mismatch is responsible for the national rise in unemployment since the recession. One recent analysis found that mismatch could explain at most about a third of the increase in unemployment experienced in the U.S.2 The remainder of the rise in unemployment is likely due to factors that impacted all industries equally, like a shortfall in aggregate demand as consumer budgets tightened due to the financial crisis.3 Some argue that large public sector job losses4 or government policy responses to high unemployment, such as extensions of unemployment benefits,5 also played a role.

Mismatch Unemployment in Rhode Island

Rhode Island has historically had an unemployment rate roughly comparable to, though at times slightly higher than, its New England neighbors (see Figure 1). But since the start of the Great Recession, it has pulled away and experienced one of the highest unemployment rates in not only the region, but the country as a whole.

What is driving Rhode Island’s exceptionally high unemployment rate? If we look at possible explanations for the shift in the U.S. Beveridge curve – and any associated rise in unemployment – we may be able to identify factors that played an exaggerated role in Rhode Island. This could help explain why the state’s unemployment rate has been so much higher than the rest of the country’s.

The Construction Industry

The shift in the U.S. Beveridge curve may be the result of labor market mismatch caused by a sharp fall in employment in the construction sector due to the housing crisis. Between the peak of the housing bubble in 2005 and the depths of the Recession in 2008, the industry lost 3 million jobs, and laid-off workers may have a had a hard time transitioning to other sectors. Although construction only accounts for about 5% of total employment in the U.S., recent research suggests that declines in the construction industry may explain a significant portion of the national shift in the Beveridge curve and associated increases in unemployment.6

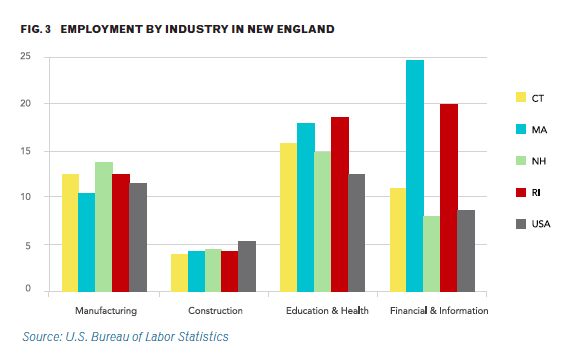

Could job losses in the construction industry also explain the exceptionally sharp rise in unemployment experienced in Rhode Island? As Figure 3 shows, pre-recession employment in construction was not noticeably higher in Rhode Island than in other New England states and was substantially lower than in the U.S. as a whole. So it is unlikely that construction job loss explains why the state’s unemployment rate has been so much higher than in the rest of the country.(b)

Fast-Growing Firms

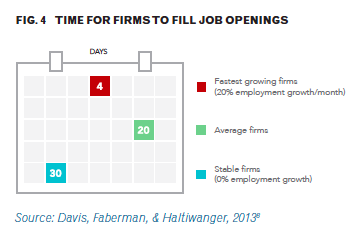

Another potential explanation for the shift in the U.S. Beveridge curve is related not to labor market mismatch, but instead to the types of companies hiring. This argument focuses on the behavior of fast-growing firms, which typically fill job openings much more quickly than stable firms.7 A firm that is replacing a departing worker will take longer to fill that opening than an expanding firm that is hiring for new positions. If the Great Recession adversely impacted fast-growing firms more than stable, slow-growing firms, that effect could account for the shift in the Beveridge curve – the firms that typically hire most quickly would account for less hiring, thereby lowering the rate at which open jobs are filled.8

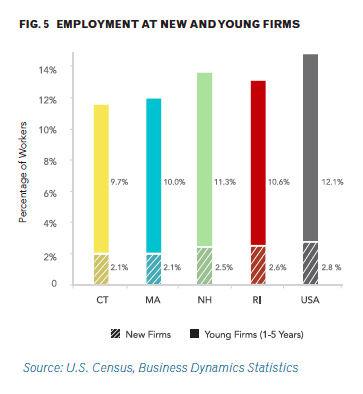

Did fast-growing firms play a role in Rhode Island’s high levels of unemployment? New and young firms (those less than five years old) tend to be the fastest growing. As Figure 5 reveals, Rhode Island actually has lower employment at new and young firms than the nation as a whole. This suggests that trouble at fast-growing firms didn’t play a particularly important role in raising Rhode Island’s unemployment rate, compared to the rest of the country.

In short, two possible explanations for the shift in the U.S. Beveridge curve – the troubles faced by the construction industry and fast-growing firms during the Great Recession – do not appear to explain why unemployment was so much worse in Rhode Island than in the rest of the country.

Other Explanations for Rhode Island’s Unemployment Spike

Educational Attainment

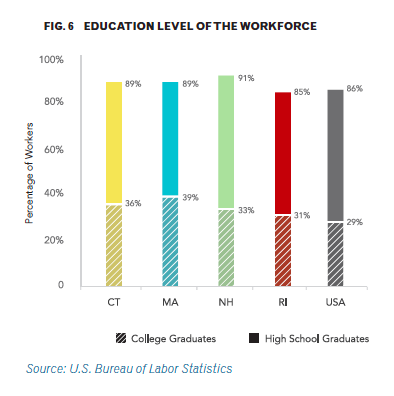

One factor that may have played a role in Rhode Island’s high unemployment rate is educational attainment, an area where the state lags behind its counterparts. As Figure 6 shows, the state’s labor force is markedly less educated than the workforce of other states in New England, in terms of both high school and college graduates. This is significant because research demonstrates that unemployment tends to spike more sharply during recessions for workers with lower educational attainment.9 Furthermore, if labor market mismatch is a factor, low levels of education can create obstacles to transitioning workers from low- and middle-skilled industries to higher-skilled industries. Therefore, differences in educational demographics are likely a substantial factor in the sharper rise in unemployment in Rhode Island relative to the rest of New England.

Disparities in educational attainment, however, are unlikely to be the whole story. Educational attainment in Rhode Island roughly matches national averages, and the state’s workforce is better educated than the workforce of many other states that did not suffer as heavily from unemployment during the recession.(c) Moreover, differences in educational attainment are a longer-term trend and likely do not explain why Rhode Island’s unemployment rate has become so much greater than the rest of the country only in recent years.

Household Wealth

Another potential explanation for the sharp rise in unemployment in Rhode Island is a drop in household wealth due largely to the housing crisis and its effect on home prices. As a recession reduces families’ incomes and wealth, they spend less, leading to lower profits for local businesses, who may lay off workers in response. According to one study, a decline in housing wealth was responsible for nearly half of the national increase in unemployment during the Great Recession.3

Household wealth was certainly hit harder in Rhode Island than in neighboring states during the recession. In Providence County, housing net worth fell 17% from 2007 to 2009,3 while the largest counties in Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts experienced less severe contractions in housing wealth.(d) The negative impact of the recession on household wealth and thus on consumer demand could plausibly account for the more severe rise in unemployment experienced in Rhode Island compared to its neighbors.

Unemployment Benefits

A final factor to consider is Rhode Island’s extension of unemployment benefits for a longer period of time than its neighbors. At the end of 2012, for instance, Rhode Island offered 99 weeks (nearly 2 years) of unemployment benefits, while Massachusetts and New Hampshire provided only 40 weeks. This differential is partly a function of the fact that unemployment rose more in Rhode Island than in neighboring states, but it may have had unintended consequences.

Recent research at the national level indicates that extensions of unemployment benefits beyond the typical 26 weeks may have elevated the U.S. unemployment rate by as much as 3.3 percentage points in 2010 and 2.5 points in 2011.5 As for Rhode Island in particular, since the expiration of extended benefits in December 2013, unemployment dropped from 9.2% to 6.8% by the end of 2014 – one of the fastest declines in the nation. However, the view that unemployment extensions raise the unemployment rate remains a contested area of research among economists.

Education & Workforce Development as a Solution to Unemployment

One clear way to address labor market mismatch is to ensure workers have the skills and expertise needed for available jobs. In both national and state discussions of weak employment and wage growth over the last decade, the focus has often turned to education and workforce development as a way to ensure that workers are a fit for jobs. What role should these policies play in Rhode Island’s recovery from the Great Recession and its long-term strategy for economic competitiveness?

Education and workforce development programs carry obvious benefits for workers by allowing them to modernize their skill sets and train in specializations that are growing.(e) These programs can be carefully targeted to address circumstances unique to a given state or region or to help retrain particular groups of workers. Research on the impact of workforce investment programs has found mixed results depending on the local context and the type of program, but overall it suggests that there are some benefits to workers in terms of higher employment rates and wages.10

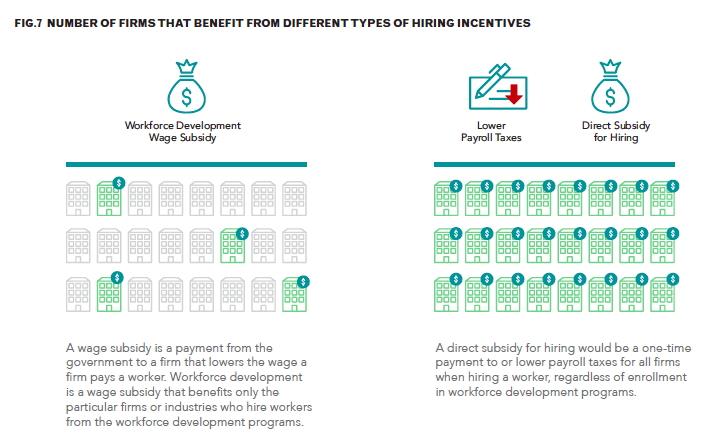

While publicly-funded education and workforce development programs have a number of benefits, they are not always the most effective solution for getting people back to work quickly. In a time of high unemployment, such policies act as a wage subsidy by lowering the effective cost of hiring a worker. A better trained worker provides greater value for a firm at any given wage, inducing firms to do more hiring. However, this subsidy benefits only the particular firms and industries who hire workers from workforce development programs, and thus may not deliver the most effective return per dollar spent. A more direct wage subsidy – either through a reduction in the payroll taxes paid by firms or a direct subsidy for hiring – would have similar effects on employment but would be more transparent and perhaps more cost-effective.

As an alternative or complement to publicly-funded programs, the government can try to shift the responsibility for training workers onto private firms. When unemployment is low and labor markets are tighter, firms often invest their own resources in educating and training workers in the skills they need. Government programs that entail the hiring of workers, like public infrastructure projects, boost the demand for labor. By making the labor market tighter, these programs also indirectly encourage private firms to hire and train workers.

State governments that choose to invest in education and workforce development should also keep in mind that, while these programs deliver clear benefits to workers, states aren’t always able to keep the benefits within their borders. After receiving education or training, workers may simply leave the state and migrate to areas where jobs are in greater supply. This is an important limitation of policies that seek to reduce local unemployment solely by focusing on workforce training and development.

Moving Rhode Island Forward

My analysis indicates that labor market mismatch is unlikely to account for most of the rise in unemployment experienced in Rhode Island during and after the Great Recession. However, this does not rule out a role for labor market mismatch over the long run. A steady decline in manufacturing and comparatively low levels of educational attainment may account for some of the unemployment experienced by Rhode Island in the last 30 years.

Though policies aimed at addressing labor market mismatch, like workforce development and education programs, benefit individual workers by helping prepare them for jobs, these programs are not a panacea for what ails Rhode Island. Solutions must also focus on the business environment in Rhode Island, informed by research to help identify the obstacles that prevent businesses – particularly new and young firms – from expansion and hiring. Furthermore, programs to reduce the burden of debts incurred during the housing boom and bust may help restore consumer demand and get Rhode Island households spending again.

Endnotes

- The historical data on job openings needed to depict a Beveridge curve is only publicly available for the U.S. as a whole, not for individual states. Thus a Beveridge curve for Rhode Island is not included in this report.

- Aysegul Sahin, Joseph Song, Giorgio Topa, and Giovanni L. Violante (2014) “Mismatch Unemployment, American Economic Review, 104(11): 3529-3564.

- Atif Mian and Amir Sufi (2014) “What Explains the 2007-2009 Drop in Employment?” Econometrica, 82(6): 2197–2223.

- Benjamin H. Harris, Brad Hershbein, and Melissa S. Kearney (2014) “A Tale of Two Jobs Gaps: Private-Sector Recovery and Public-Sector Stagnation,” Brookings on Job Numbers, Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- Marcus Hagedorn, Fatih Karahan, Iourii Manovskii, and Kurt Mitman (2015) “Unemployment Benefits and Unemployment in the Great Recession: The Role of Macro Effects” Working Paper no. 19499, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Steven J. Davis, R. Jason Faberman, and John C. Haltiwanger (2012) “Recruiting Intensity During and After the Great Recession: National and Industry Evidence,” Working Paper no. 17782, National Bureau of Economic Research. Neil Mehrotra and Dmitriy Sergeyev (2013) “Sectoral Shocks, Shifts in the Beveridge Curve and Monetary Policy,” Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University.

- Steven J. Davis, R. Jason Faberman, and John C. Haltiwanger (2013) “The Establishment-Level Behavior of Vacancies and Hiring,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(2).

- Neil Mehrotra and Dmitriy Sergeyev (2015) “Financial Shocks and Job Flows,” working paper.

- Michael W. L. Elsby, Bart Hobijn, and Aysegul Sahin (2010) “The Labor Market in the Great Recession,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- Caroline M. Francis (2013) “What We Know About Workforce Development for Low-Income Workers: Evidence, Background and Ideas for the Future,” National Poverty Center Working Paper Series No. 13-09, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, National Poverty Center.

Sidenotes

- (a) As of December 2014, Rhode Island had the fifth-highest unemployment rate in the country – 6.8% compared to the U.S. average of 5.6%. The state’s unemployment rate peaked at 11.9% in the winter of 2009/2010, while the national rate topped out at 10.0% around the same time.

- (b) Manufacturing is another industry that has been hit hard in recent years and in which laid-off workers can have a difficult time transitioning to other fields, potentially leading to labor market mismatch. However, as with construction, manufacturing isn’t more prominent in Rhode Island than in neighboring states or the country as a whole (see Figure 3).

- (c) Rhode Island ranks 35th in the U.S. in the share of its population with a high school degree and 13th for college degrees. Several states that rank below Rhode Island in educational attainment – like Texas, Oklahoma, and Idaho – nonetheless have significantly lower unemployment rates.

- (d) For example, housing net worth dropped 7% in Fairfield County, CT (home to Bridgeport and Stamford), 4% in Hillsborough County, NH (home to Manchester), and 6% in Suffolk County, MA (home to Boston).3

- (e) In the long run, workforce development programs benefit individual workers more than wage subsidies because they increase workers’ human capital. Workers with higher levels of education and training earn more and are more likely to be employed.