You spend five dollars ordering a movie on demand. Ten minutes in, you’re already bored. Do you keep watching or give up?

If you’re inclined to sit through the movie so that the money you spent doesn’t go to waste, your reasoning is not unusual.(a) People often continue pursuing fruitless endeavors because they have already contributed time, money, or effort to them. Whatever the type of cost, the logic is basically the same: “I’ve already sacrificed [money, time, or energy] so I’d might as well do [something that is a sacrifice in and of itself].”

This mistake is often referred to as “throwing good money after bad,” or if you’re talking to an economist, the sunk cost fallacy. Sunk costs are irreversible expenditures that cannot be recovered. The fallacy lies in not realizing that the money has already been spent and we cannot get it back, especially not by doing something of negative value to us, like watching a boring movie.(b) We all want the biggest bang for our buck (and our time and effort), but when we pursue this goal by sticking with a bad choice, we end up wasting more. Whether you watch the movie or not, you’ve wasted $5; the only difference is that if you watch it, you’ve also wasted two hours. A rational decision-maker considers only future costs and benefits, not past expenses.2

Though originally developed to describe behavior surrounding monetary spending, such as the likelihood to continue gambling after losing money, less tangible sunk costs have been explored by cognitive and social psychologists in the field of behavioral economics.(c) For example, cults often recruit people by first convincing them to read flyers. After this initiation, prospective members may be more likely to join because they have sunk their time into learning about the cult.4 The time devoted to cultivating and defending a belief can also become a sunk cost, which helps explain why passionate debates may continue long after a position is proven wrong.(d)

History demonstrates that the risks of the sunk cost fallacy can be more significant than simply wasting two hours watching a bad movie. It can also lead decision-makers to waste exorbitant amounts of money and even human lives in pursuit of doomed endeavors.2 In game theory, the sunk cost fallacy is referred to as the Concorde fallacy, a reference to the Concorde aircraft, whose construction the British and French governments continued to fund long after the project’s inefficiency and unprofitability became clear. “I have already invested so much in the Concorde airliner … that I cannot afford to scrap it now,” said one investor.2 Military and foreign policy leaders have also fallen victim to the fallacy. During the Gulf War, Sergeant Robby Felton said, “Too much money’s been spent, too many troops are over here, too many people had too many hard times not to kick somebody’s ass.”2

This thought process happens even when there is no cost to public image or pressure to appear consistent. Arkes and Blumer, for example, arranged for a theater to sell season passes at three different prices, each to an equal number of people at random.1 People who bought costlier passes attended more performances throughout the season, even though nobody was counting (they didn’t even know they were in an experiment).

Why is the sunk cost fallacy so pervasive and convincing? People tend to overgeneralize rules of behavior that are often, but not always, beneficial.5 Platitudes like “get the biggest bang for your buck” and “don’t be wasteful” are meant to apply to future spending decisions, such as ordering the cheapest menu item.(e) When applied to the decision to finish an already-purchased meal, these maxims might help delay your next meal if you can’t save leftovers – or “squeezing pennies” could cause trouble squeezing into your clothes.

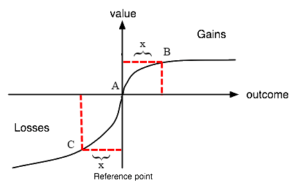

In addition to overgeneralization, the behavioral economics principle of loss aversion helps explain the sunk cost fallacy. Loss aversion is the human tendency to be more troubled by a loss than pleased by a comparably sized gain.(f) Because of loss aversion, people are more likely to take risks to recuperate losses than to incur equivalent gains.6 Though it may seem paradoxical to follow through with bad investments to avoid losses – and this incongruence is indeed what makes the act a fallacy – unwillingness to accept defeat may drive people to tighten their grasp on investments that rational actors, who don’t feel the emotional sting of a loss, would release. For example, gamblers bet more after losing money, with the hope to regain it, than when they start gambling with a clean slate.7

This graph shows how people value losses and gains differently. The steeper slope for losses represents their stronger emotional impact relative to gains.8

Another explanation for the sunk cost fallacy is cognitive dissonance, which is the discomfort that comes from espousing conflicting beliefs.9 To avoid this feeling of dissonance, people may alter their perceptions of external situations to match their internal beliefs. In the case of sunk costs, people don’t want to see themselves as wasteful, so they make decisions that attempt to fully utilize everything they have worked or paid for. People also don’t want to see themselves as bad investors, so they may hold out hope that their investments will magically pay off, even when external evidence points to failure.(g)

Supporting the cognitive dissonance hypothesis are a number of studies showing that people often try to convince themselves a wasted effort was worthwhile after the fact. In one experiment, people who read about the same investment rated it as more profitable when the investment was already made, demonstrating that the tendency to view investments as valuable can be an effect, as well as a cause, of investment choices.10 Similarly, people have higher confidence in a racehorse when they have already bet money on its victory than when they are about to put the same amount of money down.11

Do any of the above scenarios or reasoning strategies sound familiar? Does the thought of giving away a ticket for a show you don’t even want to see make you panic? Do you hoard useless items because you can’t sell them for the same price you bought them for? If so, it sounds like you have succumbed to the sunk cost fallacy.

As with most cognitive biases, mere awareness of this fallacy is fairly useless; studies show that even economics students who have learned about sunk costs fall victim to it.1 But people who work in areas especially prone to the sunk cost fallacy can try to look out for it. For example, financial advisors should be aware that stockholders are often reluctant to sell stocks that have fallen after their purchase because that lost value is a sunk cost. But if investors hold onto stocks that keep declining, they lose an opportunity to cut their losses and to reap the benefits of a U.S. tax policy that favors selling after losses are incurred.7

To address the sunk cost fallacy in your day-to-day life, one approach is to think of each fork in the road as a clean slate. Ask yourself what you would do if you had not yet put anything toward that endeavor. Don’t think of possible gains as opportunities to regain sunk costs.7 Though you can’t compensate for past losses, you can maximize future gains by making the best decision, one that doesn’t honor sunk costs. So while the time you just spent reading this article is a sunk cost, you can still maximize future gains by taking what you just learned into account in your next big decision.

Endnotes

- Hal R. Arkes and Catherine Blumer (1985) “The Psychology of Sunk Cost,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 35: 124-140.

- Reid Hastie and Robyn M. Dawes (2010) Rational Choice in an Uncertain World: The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making, SAGE publications.

- Paul J. H. Schoemaker (1982) “The Expected Utility Model: Its Variants, Purposes, Evidence and Limitations,” Journal of Economic Literature, 20: 529-563.

- Robert P. Abelson and Deborah A. Prentice (1989) “Beliefs as possessions: A functional perspective,” Attitude Structure and Function, edited by Anthony R. Pratkanis, Steven J. Breckler, and Anthony G. Greenwald, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: 361-381.

- Hal R. Arkes and Peter Ayton (1999) “Sunk Costs and Concorde Effects: Are Humans Less Rational Than Lower Animals?” Psychological Bulletin, 125(5): 591-600.

- Robert Jervis (1992) “Political Implications of Loss Aversion,” Political Psychology, 13(2): 187-204.

- Richard H. Thaler and Eric. J. Johnson (1990) “Gambling with the House Money and Trying to Break Even: the Effects of Prior Outcomes on Risky Choice,” Management Science, 36(6): 643-660.

- Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky (1979) “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk,” Econometrica, 47(2): 263-291.

- Elliot Aronson and Judson Mills (1959) “The Effect of Severity of Initiation on Liking for a Group,” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 59: 177-181.

- Hal R. Arkes and Laura Hutzel (2000) “The role of probability of success estimates in the sunk cost effect,” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 13(3): 295-306.

- Robert E. Knox and James E. Inkster (1968) “Postdecision Dissonance at Post Time,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(4): 319-323.

Sidenotes

- (a) In one survey, over half of respondents said that, if they accidentally booked two trips in one weekend – a $50 trip that they were really looking forward to and a $100 trip that they were less enthusiastic about – they would go on the $100 trip.1

- (b) It may be rational to stick with the movie if you don’t have enough time or money to do something else, but these past circumstances are only relevant insofar as they influence future outcomes. One might compare this paradigm to foraging theory in biology, which posits that if an organism’s risk of traveling is greater than the risk of remaining at a non-optimal patch of land, it makes sense to stay.2

- (c) Behavioral economics combines psychology, neuroscience, applied math, and other fields to describe how people make economic decisions, rather than prescribe ideal decisions, as traditional economics often does. While classic economics measures payoffs in terms of expected value – each possible amount of money gained or lost times each probability of receiving or losing it – behavioral economists often speak in terms of expected utility, each possible subjective reward or punishment times each probability of receiving it.3

- (d) The researchers who propose that beliefs can be sunk costs did so within a general framework of beliefs as possessions, in which people come to understand beliefs by thinking of them as items that they own.4

- (e) Children, who have internalized fewer truisms like “don’t be wasteful,” show the fallacy less often than adults. Other animals do not appear prone to the fallacy in their survival decisions.5

- (f) Psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky established the phenomenon of loss aversion through a series of questionnaires, including one that showed people were more likely to support a public health intervention framed in terms of the percentage of a population that would survive an epidemic than the same one framed in terms of the reduced number of deaths.6

- (g) According to Aronson and Mills’ effort-justification paradigm, people assign increased value to hard-earned rewards to justify the effort of attaining them.9 Aronson and Mills gave participants lists of words to read out loud as a prerequisite for a sexuality discussion group. Some candidates had to read obscene words and explicit passages, while others were given a list of mildly sexual words. The ensuing discussion underwhelmed participants with vague and technical descriptions of lower organisms’ secondary sexual characteristics. However, those who recited the obscene prerequisite words rated the discussion more interesting and enjoyable than the other group. The authors concluded that participants did not want to feel foolish enough to embarrass themselves for “one of the most worthless and uninteresting discussions imaginable.”